Seldom Sung – Some (Un)common Women from Meghalaya

Ka Maitphang ba la shim na ka kot ‘KA MARYNTHING RUPA’

Ka Maitphang :

Ym don u kynja ba don jingim, naduh u briew haduh u mrad u mreng uba iaid ha sla khyndew, ki sim ki doh kiba her ha suiñ, ki dohkha bad kiwei ki jait jingim kiba don hapoh um bad wat ki dieng ki siej, ki syntiew ki skud, ki jingthung jingtep kiba ym ktah da ki sur jingtem jingput ne jingrwai. Ki puriskam ki Greek ki ong ba haba u tem u Orpheus wat ki maw ruh ki khih. Ki riewstad mynta pat ki pynshisha ba ki jingthung ki sei ki plung bha haba ki iohsngew ia ki sur jingrwai.

Ki jingrwai, khamtam kito kiba la shna bha, kata, kiba iabiang ka dur bad ka sur ki ngam shaduh ka dohnud u briew bad ki ktah ia ka jingsngew jong u. Haba nga ong ka dur bad ka sur, nga mut ki ktien ka jingrwai bad ki sur ba la shna ban pyniahap bad ki ktien ka jingrwai. Dei kane ka jingpynbiang ia ki ktien bad ki sur kaba la pynim slem-slem ia ki jingrwai kiba rim bad shisien ba la iohsngew ia kine bad la nang ia ki, ki neh sah ha ka jingkynmaw. Lym kumta i Bah L.Gilbert Shullai in ym da la lah ban kynmaw ia ki jingrwai kiba i la iohsngew, nga ngeit, naduh ba i dang khynnah. Wat u nongrwai ruh haba u rwai ia ki jingrwai kiba rim u da pynpaw ba ki ktah ia ki dohnud bad ka jingpyrkhat jong u, kata, kumba ong ha ka ktien Phareng, u rwai da ka ‘expression’.

Baroh ki jingrwai ba la shna bha ia ki, ki don la ka por ban rwai ia ki. Don na ki kiba dei ban rwai mynstep, donpat ban rwai mynmiet. Don na ki kiba dei ban rwai haba sngewsih bad don pat kiba dei ban rwai haba sngewbha. Don kiba iadei ban rwai haba sngewkynjah sngewblaw bad don kiba iadei ban rwai haba paidbah. Ki don ki sur kiba ktah ia ka jingieit samla bad don ki sur kiba pynsngewtriem ne pynshyrkhei.

Haba nga dang samla khynnah bad nga leit bud leit jingleit ia u Sahep Bishar (Dohlieh) sha Mawphlang, katba nga dang shongkai ha ka karma ha ïing u Lyngdoh Mawphlang ha kaba la pynbeit ia nga ban sah, uwei u nong-Mawphlang u wan wad ia nga hadien ba u la syaid bad shongshit bha bad u rwai artat ia kawei ka jingrwai kaba la rim bad kaba ju iarwai bha ha kita ki por.

‘I’m only painting the Clouds with Sunshine’.

Ynda la iashongkai, nga sa sngewthuh ba u long u briew uba shem lanot bha. Kumta ngi iohi hangne ba ka jingrwai kaba la shna bha bad dur bad sur ka ktah haduh katno?

Kawei pat kaba pynshoh ia ka jingrwai ka long ka jingbuh kaba biang ia ka rukom tied kaba ki ong ka Timing ne Measure, la ka dei kaba shi-dieng shi-dieng, arsaw, laisaw kum ki Foxtrot, ki Waltz, ki Rhumba, ki Samba, ki Bequine Tempo, ki March. Ki don ki jingrwai kiba suki bad ki don ki jingrwai kiba stet. Ha ki por hyndai haba dang shlei ka Iewduh da ki dorji phin iohsngew ia kine ki rukom rwai ha ka jingryntih ka jingiaid ki shalyntem ka kor suhjaiñ ba la kynjat da ki kjat u nongrwai ne u dorji, lane ia ki ‘Walts’ haba kynoi khun ka kmie ne haba dril ki khynnah bad kumta ter-ter.

Mynta ha kine ki por pat imat la shu shna ki jingrwai kiba shisur tang ban shu pynsmiej ia ki kjat ki samla ne ki basan kumjuh ban shad lymmuh. Tang shu iohsngew ia ki jingrwai, la shu tied klumar ia ka miej ka shuki bad ieng bad shad katba mon, kata ban Jive, Rock ne Disco. Ha ki samla jong ngi mynta lei-lei imat la shu iashna klumar haduh ba ka dur kam iadei bad ka sur ne ka sur kam iahap bad ka dur. Bun na ki jingrwai la shu pyniahap jubor ia ka dur bad tan jubor ia ka sur. Teng-Teng ia ka dur ruh ym sngewthuh bad ka sur ruh kam pei ia ka skhor. Phin sngap ba don ki Cassette Khasi mynta kiba ka dur ne ktien kaba mut shawei bad ka sur pat kaba thew shawei. Kumba ong u paralok jong nga ba bun ki Cassette Khasi te imat ki long Three in One – ka dur la ka jong, ka sur la ka jong, bad ka jingkynnoh ia ki ktien la ka jong. Te namar kata kim biang keiñ.

Kawei pa kawei ka laiñ ba nyngkong jong ki jingrwai ha kane KA MARYNTHING RUPA jong i Bah Gilbert ka pynkynmaw ia nga ia ki por kiba ki jingrwai Phareng ki la long don long snam ha u nongrwai nongtem Khasi bad la i kumba kin long ka bynta jong ka Culture jong u Khasi hi. Kane ka lah ban long, lehse, bym pat mih ki nongshna jingrwai Khasi kiba tbit ban shna ki jingrwai kiba biang bad dur bad sur. Ki jingrwai Khasi ba shna ha kito ki por ki long kito ki jingrwai ba la shna dur bad pyniahap ha ki sur Dkhar bad ba rwai ne tem ia ki haba ialehkai theatre kum ha Jowai, Mawphlang, Mawngap, Marbisu, Sohra, Mawsynram bad ha Seng Khasi ha Mawkhar.

Ka jingbang ia ki jingrwai Phareng ha ngi ki Khasi, imat ka long hadien ka Thma Bah kaba Nyngkong, kata hadien ka snem 1918 ynda ki Khasi jong ngi ki la iawan na France bad Mesopotamia. Ynda la wan sa ka Thma Bah kaba ar, la nang jur shuh-shuh ka jingiarwai Phareng.

Haba nga kynmaw ia ki por shuwa ka Thma Bah kaba ar, ka wan shat ha nga ka dur jong ki radbah ha ka put ka tem, ka rwai ka siaw. Nga kynmaw ia u Bah Rishot uba tem Bela, Bah Destar ba tem Mandolin, Bah Kelly Diengdoh ba tbit bha ban tem Bela, Accordion, Clarinet bad kiwei- kiwei ki jingtem jingput, Bah Syndor ba put Clarinet, Bah Jokes ba tem Accordion, Bah Bihsar ba tem Banjo, Bah Baden ba tem Ukelele, Bah Reban ba put Besili. Nangta sa ki jong u Bah Theo Lyngdoh, Bah Soverine, Bah Orgheus Pakma, Bah Owen Rowie, Kong Trilian Pariat kiba tem Bela, Bah Vie Swer, Bah Garlile Diengdoh kiba tem Hawaiian Guitar, Bah Din Swer ba tem mandolin.

Nga dang kynmaw haba tem u Bah Kelly Diengdoh shiteng miet ia ka jingrwai “Ramona” ha surok Jaiaw, baroh ki jingkhang – ïit ki mih jingshai ban sngap ia ka sur kaba mih na ka Bela jong u bad kumjuh ruh haba put Clarinet u bah Syndor. Nga la iohsngew ruh ia ki kti ba pnah jong u Bah Rishot Khongwir ha ka Bela bad u Bah Destar Khongwir ha ka Mandolin bad nga la ioh ka lad ban iatem lang bad ki shisien arsien ia ki jingrwai kiba nga dang kynmaw kum ka jingrwai “South of the Border”, “Little Girl of my dream”,”After the Ball”, “Merry Widow”, “ Three O’clock in the Morning”, “Colonel Boogie” bad bun kiwei kiwei ki jingrwai. Ha kata ka por nga la pyntbit ialade ban tem Mandolin bad Bela.

Sngewtynnad ban Kynmaw ia kitei ki radbah nongtem ba kida pyntbit bha ialade shuwa ba kin mih pyrthei bad kida nang ruh ban pule Music, kata ia ka Staff. Ki long ki briew kiba khraw ka jingmut jingpyrkhat bad kim ju pynthut ia kiwei. Ka jingiatem ha kito ki por ka long ka jingsngewtynnad ialade bad ka jingpynsngewtynnad ia kiwei. Haba ki iatem ha surok, ym ju don ba pynwit ne kynroi ia ki. Don na ki katba kim pat sngewtynnad ne syiad bha, kim ju sdang ban iatem hynrei ki ialeh ka pynbeit ksai. Uwei u rangbah u iathuh ba haba ki leit iatem ha Shillong Club ha ki por ba dap ka Club da ki Dohlieh, ynda u Chowkidar u lum ia ki bitor, u lap katto-katne ki bitor khlem lavel ba la set da ka sla.

Sngewtynnad ban Kynmaw ia kitei ki radbah nongtem ba kida pyntbit bha ialade shuwa ba kin mih pyrthei bad kida nang ruh ban pule Music, kata ia ka Staff. Ki long ki briew kiba khraw ka jingmut jingpyrkhat bad kim ju pynthut ia kiwei. Ka jingiatem ha kito ki por ka long ka jingsngewtynnad ialade bad ka jingpynsngewtynnad ia kiwei. Haba ki iatem ha surok, ym ju don ba pynwit ne kynroi ia ki. Don na ki katba kim pat sngewtynnad ne syiad bha, kim ju sdang ban iatem hynrei ki ialeh ka pynbeit ksai. Uwei u rangbah u iathuh ba haba ki leit iatem ha Shillong Club ha ki por ba dap ka Club da ki Dohlieh, ynda u Chowkidar u lum ia ki bitor, u lap katto-katne ki bitor khlem lavel ba la set da ka sla.

Ha ki snem kiba kham hadien la mih sa uwei u nongtem Bela uba tbit bha bad uta u dei u Bah Besterwel Soanes. Ki ong ba haba tem u Bah Besterwel ha ka Concert ha Gauhati Cotton College, la hap cancel lut ia ki Item kiba hadien namar ki paitbah ki ia kwah ia u Bah Besterwel ban tem baroh shimiet.

U nongtem Bela uba la palat liam ia baroh ki nongtem Khasi pat u dei u Bah Ramsong uba la khlad noh haba nga dang khynnah bad ngam pat iohsngew ia ka jingtem jong u, ne kynmaw ia u. Ki ong ba haba tem u Bah Ramsong wat ki Mem kiba la nang bha ban tem Piano ki shitom ban iabud ia u haba ki iatem na ka kot (Music Book), kata da ka Staff. U lah ban tem ia ki sur Classical kiba eh katno-katno ruh namar u da nang bha ia ka Staff. To, la dei ban tei mot ia uba kat une u rangbah nongtem uba ym pat ju don kat ma u ha ka Ri jong ngi bad ban ym mih shuh ruh kiba kat ma u, khamtam mynta ba la shu tem ne rwai tynneng khlem da sngewthuh ne nang ia ka Music ( nga mut Staff Notation bad Tonic Solfa).

Ha ka Thma Bah kaba ar ha ki snem 1939-45, ka la don ka jingwan poi ki shipai dohlieh, ki Johny bad Tommy hangne ha shillong bad sdang shongshit ka rwai ka tem sur Phareng ka shnong ka thaw. Ha kitei ki snem ki wan poi sa ki kynhun put kynhun tem bad nongialeh kai pynbyrngia ki dohlieh ba ki khot ki ENSA kiba wan khnang ban pynsngewbha ia ki shipai kiba don ha Shillong. Jan man ka miet ki iarwai iaput iatem bad ialehkai ha Garrison Theater Cantonment ha kaba don ka jingpyni film phareng ( Cinema ) man ka sngi. U Paitbah Khasi u tuid man ka sngi sha Garrison Theater, ym ban peit eh ia ki film hynrei ban iohi ia ki nongrwai nongtem ne nongialehkai bad ban iarwai hapoh Cinema. Shwa ban sdang ka ‘show’ ju don ka jingiarwai lang ia ki sur kiba sngewtynnad kiba ki ktien la pyni ha ka Screen kum –

You are my sunshine, Lily Marlane,

Sierra Sue, Goodnight Irene,

Lay that pistol down, With someone like

you, White Cliff of Dover,

Slow boat to China, Home on the range,

My wild Irish Rose,

Rose of Tralee; bad bun kiwei-kiwei ki jingrwai.

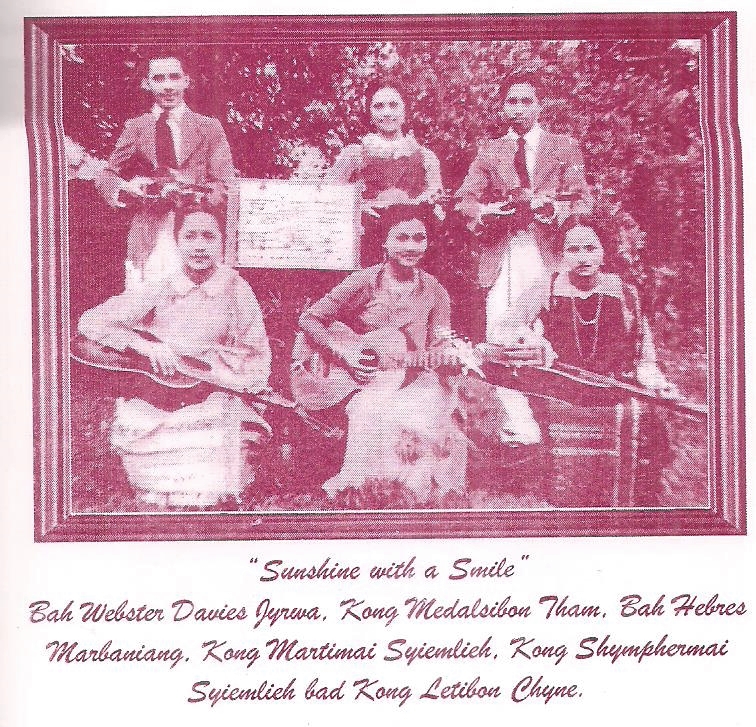

Ha katei kajuh kapor la mih shuh-shuh ki nongrwai nongtem Khasi kiba nang bad pawkhmat bha kum ki jong u Bah John Shome, Bah Hebress Marbaniang, Kong Semina, Bah Rosbell Chyne, Bah Gretan Sun, Bah Richard Nalle, Bah Beriwell Kyndiah, Bah Lebi, Bah Filkin Laloo kiba tem Bela ; Bah Noel Arbor Khongwir bad Lursingh Jyrwa kiba tem Mandolin ; Bah Thomlin, Bah Kynsai Nalle, Kong Icydian Swer kiba tem Hawaiian Guitar ; Bah Cyril Lyngdoh, Bah Harvey kiba tem Spanish Guitar. Dei ha kane ka por ba u Bah Andreas Shome u la plie ia ka Shillong Music School ha Umsohsun. Kane ka skul ka la long kaba nyngkong ban hikai jingtem bad ka la lah ban ai jingmyntoi ia kiba bun. Hynrei hadien ba u Bah Andress um don shuh, kane ka skul kala duh noh bad ym don skul hikai jingtem shuh haduh mynta.

U bah John Shome u la pyni ia la ka jingtbit tem jong u ha ki Concert kiba bun. U Bah Gretan Sun pat u don ki kti kiba jem. U Bah Noel Arbor Khongwir u long lehse uba tbit tam ka mandolin, nga la iohsngew ia u Bah Arbor ha ki ‘Peak Hour’ ba u tem ia ki Tango, kum ia ka ‘Jealousy’ bad ‘La Cumparsita’ ryngkat bad ki jong u De Mello bad De Suza. U Bah P.Ripple Kyndiah ruh u long uwei na ki nongtem mandolin ba tbit bad ba paw bha. Nga la iatem lang shisien ia kawei ka Concerto ha Dinam Hall ryngkat bad ki jong I Kong Trilian, Bah Orpheus, Kong Semina, Richard Nalle ha kaba la pynlyngngoh ia ki paidbah. Ki nongrwai jingrwai Phareng kiba radbah ruh ki la mih ha kine ki por hadien ka Thma Bah kaba ar kum ki jong u Bah Jes Nongkynrih uba lah ban rwai baroh shimiet bad la ka Guitar bad uba lah da shisha ban rwai Phareng. Nga dang kynmaw ia ki katto katne ki jingrwai ba u rwai kum – “Sheik of Araby”, “Slow boat to China”, “I’ll get by”, “Lay that pistol down”, “come on and hear” bad kiwei kiwei. U Bah Jes u lah ban rwai sngewtynnad wat lada sah sa tang ar tylli ki ksai ha ka Guitar jong u.

La don ruh ki nongrwai kum ki jong u Bah Hem Swett uba la palat liam kum u Tenor Voice. U Bah Hem u lah ban rwai ia ki jingrwai u Slim Whitman ia ka “Indian Love Call”, “China Doll” bad “May Time” jongu Nelson Eddie bad ka Jenet Medonald bad kiwei kiwei ki jingrwai kiba syiang da u ryndang uba um bad jail bha. Ki ong ba haba u rwai bad tem Piano ha kawei ka Hotel heh ha Calcutta, ki Dohlieh ki shu kyrngah khlieh bad lyngngoh ngaiñ. Mano ban klet ruh ia ka jingrwai jongu Bah Siken Swer uba don u ryndang uba sngewthiang bad ba lah ban bteng ia ki Octave sha u ‘note’ uba jrong tam khlem da don kano kano ka jingdkoh. Nga kynmaw ia kawei ka jingrwai ba u Bah Siken u rwai mynba u dang khynnah samla “Ave Maria” ha ka ktien Italian, kaba la palat ka jinglah jong u ban rwai bad ka ‘expression’ haduh wat ki Catholic Father ruh ki la lyngngoh. Ym don jingthut ne jingkynnoh bakla ia ki ktien bad la sngew kumba tem da ka Bela. Nangta mih sa u Bah A.B.Wahlang ba ju tip kum u bah Toto ha ki Club kiba heh ha Calcutta ; u la pynpaw ia ka jingtbit ban rwai ia ki jingrwai Phareng bad ka kyrteng jong u ka la mih man ka por ha ki kot khubor Phareng. Ha ki snem kiba kham hadien lah mih ka kynhun tem “The Dynamite” kaba long ka band group kaba sngewtynnad bad kaba la neh shipor.

Ha ka snem 1948 ki samla nongtem Jaiaw kila ia lum lang bad ki la pynmih ia ka kynhun tem kaba ki la ai kyrteng – “Jaiaw Orchestra”. La jied ia nga kum u Nongialam (Leader) jong ka Orchestra bad nga la trei shitom bun-bun snem ban pynbeit bad ialam ia ka “Jaiaw Orchestra”. Ki dkhot kiba nyngkong jong ka Orchestra ki long :-

- Bah Bonarwell Lyngdoh – Bela bad Guitar.

- Bah Harold Nongkynrih – Mandolin, Ukelele bad Bela.

- Bah Everland Syiemlieh – Mandolin bad Piano Accordian.

- Bah kyndwer Khongwar – Bela.

- Bah Rosswel Chyne – Bela.

- Bah Soken Kharshandi – Spanish Guitar bad Bango.

- Bah Betterland Syiemlieh – Spanish Guitar.

- Bah H.Methington – Hawaiian Guitar.

- Bah Arthur Warren – Harmonica bad Drums.

- Bah Hubert Dkhar – Spanish Guitar.

- Bah Mawrong Kharsati – Spanish Guitar bad Bango.

- Bah Borwin Nongrum – Maracas bad Guitar.

- Bah Osland Nongrum – Bela.

- Bah John Ryntathiang – Bela.

- Bah Sainmanik Syiemlieh – Spanish Guitar.

- Bah Clader Rynjah – Spanish Guitar.

Nalor ba ki dei ki nongtem, u Bah Sainmalik Syiemlieh bad u Bah Calder Rynjah ki dei ruh ki nongrwai.

Hadien pat la wan iasoh sa kine :-

- Bah Marshal Blah – Bela.

- Bah Fredie Cholas (na Riatsamthiah) – Spanish Guitar.

- Bah Dodo (na Laban) – Spanish Guitar.

- Bah Orlando (na Mawlai) – Spanish Guitar.

- Bah Phil Lyngdoh – Spanish Guitar.

- Bah Horil – Bela.

- Bah Diren Swett – Bela.

- Bah Aibor Lyngdoh – Spanish Guitar.

- Bah Defend War – Bela.

Nalor kitei ki regular members ki don sa kiwei pat kiba ju wan iasoh kum ha ka concert –

- Bah Pires – Drums.

- Kong Stelly Rynjah – Piano.

- Kong Eugene Rynjah – Piano.

- Bah Phersingh Lyngdoh – Piano.

Ki Tham Sisters, kata I Kong Deidora Tham, Kong Ivora Tham bad Kong Balmora Tham ki long ki nongrwai kiba bang tam ha kito ki por bad kine ki rwai bad katei ka Jaiaw Orchestra wat la kim long ki regular members.

Ki Tham Sisters, kata I Kong Deidora Tham, Kong Ivora Tham bad Kong Balmora Tham ki long ki nongrwai kiba bang tam ha kito ki por bad kine ki rwai bad katei ka Jaiaw Orchestra wat la kim long ki regular members.

Katei ka Jaiaw Orchestra ka la neh bun-bun snem. Ka la pynlong ki Concert kiba bun ban iarap ia ki Hospital, ki Skul bad ban pynmih pisa na ka bynta kiba shem lanot ha ki Flood bad Jumai. Ki pynlong Anniversary man ka snem. Ki Opening Number ha kitei ki concert ka long ka “Danawelin” ne “Waves of the Danube” bad ka closing number pat ka long “Look for the Silver lining” ha kaba baroh ki nongtem ki nongrwai ki iashim bynta lang.

Katei ka Orchestra ka pynbit ban tem ia ki jingrwai Phareng kum ki Waltz, ki Rhumba, ki Samba, ki Tango, ki Bequine Tempo, ki Quick Steps bad Slow Steps bad kiwei-kiwei. Nalor ki jingiatem ki la pynmih ruh ki short plays kum “Discovery”, “Bishop’s Candlesticks” ha ka jingpynbeit jong u Bah B.R.Dohling. Ki Tham sisters ki la rwai bun bun tylli ki jingrwai ha kitei ki Concert, bad ki jingrwai ha ki ryndang ba bha bad ka jingryntih jong ki ka la pynlong ia ki nongpeitkai ban ym ngiah ban sngap ia ki ba ki rwai ia ki jingrwai kum – “Harbour Lights”, “My Happiness”, “Souvenir”, “Juanita”, “Sweet Marie”, “Mexicali Rose”, bad kiwei-kiwei.

Kumjuh ruh u Bah Sainmanik Syiemlieh bad Bah Clader Rynjah ki la long ki nongrwai kiba don ka bor bad ryndang kaba sngewtynnad bad ki rwai bad ka “expression”, kata ka dohnud bad ka jabieng ki iatrei lang. Katto-katne na ki jingrwai u Bah Sainmanik Syiemlieh ki long – “I love those dear hearts”, “Have I told you lately”, “Broken Hearts”, bad ki jingrwai u Bah Clader Rynjah pat – “Damino”, “Begin the Bequine”, “Delilah” bad kiwei-kiwei.

Ha kane ka por la mih sa uwei u samla nongrwai na Jaiaw, u Bah Markos Sawian uba don ka ryndang ba bang bad ba um bha bad ba lah ban rwai ia ki jingrwai kiba eh jong ki Platters kum – “Only You”, “Twilight Time”, “Great Pretender” bad kiwei-kiwei.

Ki Warbah Sisters, kata I kong Merinda Warbah, kong Itymon Warbah bad kong Liomon Warbah ki long kawei pat ka group kaba tyngeh bha ban rwai bad iamir bha ki ryndang. Ki ju rwai bad ka Jaiaw Orchestra kum ia ki number – “Lightning Express”, My Lonely Footsteps”, “Carolina Moon”, “Tennesse Waltz” bad kiwei-kiwei ki jingrwai.

Ngi ju ialam ha kito ki snem ia ki katto katne ki nongtem bad nongrwai kiba tbit na ka Orchestra ban ia tem ha ki “Annual Meet” jong ki Sahep Bakisha ha ki Club kiba heh ba heh sha Assam kum ia u Bah Bonerwell Lyngdoh (Guitar), Bah Everland Syiemlieh (Piano Accordian), Bah John Ryntathiang (Bela), Bah Arthur Warren (Drum). Nga la ialam ruh ia kiwei pat ar ngut ki nongtem kiba tbit bha kum U Bah Noel Arbor Khongwir (Mandolin) bad Kong Eugene Rynjah (Piano).

Shuwa ban leit tem sha kitei ki Club ngi la dei ban practice da ki bnai ia ki jingrwai kiba bun khamtam kiba dang thymmai. Ha kito ki por ngi ju ioh ia ki jingrwai ha ki kot pamphlet ba ngi phah na Calcutta bad Bombay kiba don ka Staff Notation bad Tonic Solfa. Nga la dei ban pynkhreh bun spah ki jingrwai kum ki Waltz, ki Rumba, ki Samba, ki Tango, ki Foxtrot, kiBegin, ki Reels bad ban long kiba la kloi ban tem ne rwai ia kano-kano ka jingtem ne jingrwai ba ki phah ki members jong kitei ki Club. Nalor kitei ki nongtem la ialam ruh ia u Bah Sainmanik Syiemlieh bad u Bah Clader Rynjah kum ki nongrwai ki jingrwai Phareng kiba paw ha KA MARYNTHING RUPA ki long tang katto-katne na kiwei pat kiba bun ki jingrwai ba ngi la tem bha ha kita ki por. Ngi la dei ban da nang bha ban tem ban rwai namar ngi tem ngi rwai ia ki jingrwai Phareng ha ki Phareng hi. Lada rwai Phareng ha ki Khasi te ka long da kumwei pat kumba leh Sing hapdeng ki Suri, hynrei ban leh Sing hapdeng ki Sing te phi la tip hi.

Shuwa ban leit tem sha kitei ki Club ngi la dei ban practice da ki bnai ia ki jingrwai kiba bun khamtam kiba dang thymmai. Ha kito ki por ngi ju ioh ia ki jingrwai ha ki kot pamphlet ba ngi phah na Calcutta bad Bombay kiba don ka Staff Notation bad Tonic Solfa. Nga la dei ban pynkhreh bun spah ki jingrwai kum ki Waltz, ki Rumba, ki Samba, ki Tango, ki Foxtrot, kiBegin, ki Reels bad ban long kiba la kloi ban tem ne rwai ia kano-kano ka jingtem ne jingrwai ba ki phah ki members jong kitei ki Club. Nalor kitei ki nongtem la ialam ruh ia u Bah Sainmanik Syiemlieh bad u Bah Clader Rynjah kum ki nongrwai ki jingrwai Phareng kiba paw ha KA MARYNTHING RUPA ki long tang katto-katne na kiwei pat kiba bun ki jingrwai ba ngi la tem bha ha kita ki por. Ngi la dei ban da nang bha ban tem ban rwai namar ngi tem ngi rwai ia ki jingrwai Phareng ha ki Phareng hi. Lada rwai Phareng ha ki Khasi te ka long da kumwei pat kumba leh Sing hapdeng ki Suri, hynrei ban leh Sing hapdeng ki Sing te phi la tip hi.

Ha kitei ki por la mih ki nongrwai kiba tbit bha, kum ki jong u Bah A.B.Wahlang (Bah Toto) ba la leit rwai shaduh Calcutta, Bah Peter Shylla, Bah Herman Lyngdoh, Bah Bernard Khongmen U Lok Jyrwa bad kiwei-kiwei.

U nongtem Piano uba ju iarap bha ia ka Jaiaw Orchestra u long u Bah Persing Lyngdoh. U long uba la nang palat hapdeng ki Khasi ia ka Piano bad u lah ban tem ia kano-kano ka piece na ka kot namar u da nang bha ia ka Staff bad ulah ruh ban tem lyndet ia ki jingrwai kiba eh katno-katno khlem da peit na ka kot.

Sa uwei pat u nongrwai uba ngim dei ban klet u dei u bah Phrangsngi Kharlukhi. Ym ang ba u Bah Phrang u nangbha ban rwai Phareng hynrei u lah ruh ban put jingput da ka ktien. Nga kynmaw ba haba u rwai ha Gauhati ha kawei ka All Assam Inter-College Music Competition, u la lah ban pynbyrngia, kum u Bing Crosby, ia ki nongsngap kiba ia pyrta “Phrangki” “Phrangki”. Nangta wan sa ki jong u Bah Bransley Marbaniang bad Bah Khain Maink Roy ki nongrwai jingrwai Pharang kiba sngewtynnad bha.

Haba phai sha ki jingrwai Khasi ha KA MARYNTHING RUPA, ym lah khlem da iaroh ia ka sap thaw jingrwai jong i Bah Gilbert, namar kam long kaba jem ban shna jingrwai, bad khamtam da ki phew tylli. Lada la shu kylla Khasi ia ki jingrwai Phareng ka long da kumwei pat, hynrei ban shna la ki jong, ka long kaba eh lymda u nongshna jingrwai u don la ka sap. Haba nga ong ka sap, nga mut ka bor pyrkhat bad ka jinglah ia kano-kano ka kam ba u briew u trei. Hangne nga lah ban kdew khyndiat, ba don ki briew kiba thoh kot, hynrei haba ia kynduh ne kren pat bad ki pat, kim long KA KOT ; kiba bun tang ki suda jingtip. Don pat kiba ym shym thoh kot hynrei ki long KA KOT ; haba ia kren ia syllok bad ki, ki sei ia ki symboh pyrkhat kiba lah ban iarap bad pynioh jingmyntoi ne pynnoh synniang, la ka long haba shna jingrwai ne ha ka thoh ka tar.

I Bah Gilbert, la ngim ju iohi ne iohsngew ba i rwai ne tem jingtem, pynban i long uba ieit bha ia ka rwai ka siaw, ka put ka tem. Nga kynmaw ia i Bah Gilbert kum iwei na ki nongiarap kam ha ka kam kaba iasnoh bad ka jingpynlong ia ka All Assam Inter-College Music Competition ha Tezpur ha ka snem 1959. Nga kynmaw ba nga leit lang kum u Judge (ryngkat bad ki jong u Bah H.Teslet Pariat bad Bah Nando E Wankhar) sha katei ka All Assam Inter-college Music Competition, bad kata ka la long mynta la kumba laiphew san snem ei-ei. Ki la ia don ki Khasi Student’s, kum ki Competitors, kiba wan na ki College kiba pher ba pher ba don hapoh ka Gauhati University, bad kita ki la long ki jong u Bah Sumar Singh Sawian, Bah Newland Sohliya, Bah Teddy Pakynteiñ, Bah Ganold S. Massar, Bah Bevan L.Swer, Bah Neston Dkhar, Bah Densil Lyngdoh. Nalor ki jingtem ba ki tem bad jingrwai ba ki rwai marwei-marwei, la don ruh ka jingiarwai Kynhun, bad ka Kynhun kaba kynthup ia kitei ki nongrwai ka la ioh ka ‘Trophy’ kum ka kynhun kaba bha tam, bad katei ka ‘Trophy’ ka dang don haduh mynta ha iing jong nga kum ka sakhi ia ka jingtbit kitei ki rangkynsai ha ka rwai ka siaw, ka put ka tem. Ngam pat kynmaw ba ki samla khasi kin ioh kum katei ka nam lahduh bad ban ioh ka ‘Trophy’. Katba dang ia don ha Tezpur ha ki sngi ba long katei ka Inter College Music Competition la ia leit ban ia rwai bad ia put ia tem ha Mental Hospital, bad ruh ha Baptist Mission Hospital.

Nga la pule ia ki ktien bad kyntien jong ki jingrwai ha KA MARYNTHING RUPA. Nga tharai kin kham bang lada buh ia ki da ki sur Khasi, namar imat don ki jingrwai kiba ym da iahap eh bad ki sur jingrwai Phareng kumba la kdew. Ñiuma i Bah Gilbert ila lah pynpaw hi ia kata, bad la iehnoh ha ki nongthaw jingrwai ban nang ia thaw ia ki sur kat kum ka jingsngewbit jong ki. Ki don katto-katne ki jingrwai kiba ia dei ruh lada rwai da ka sur jingrwai ba la buh ha KA MARYNTHING RUPA. Ban shu ai nuksa harum : mshim ia ka jingrwai Phareng – “Colonel Boogie” lane “Bridge Over the River Kwai” ; ka jingrwai lehse kaba baroh ia nang ia ka sur, bad buh da ka dur (Ktien) ba nga la shna kham mynshuwa kumne:-

Shaphrang

Ki Khun U Hynniewtrep

Shaphrang

Ka um ka ding ia ia phi kim khang,

Lada phi iaid lang

Phi ia tylli bad ryntih lang.

Shirup

Shirup u lai ko Khon ka Ri

Naduh Rilang haduh Kupli

Ban skhem la riti

Ban sah nam burom

Ban im ka Ri.

(Webster Davies Jyrwa)

Katei ka jingrwai kan biang bha lada rwai paidbah ia ka ha ki kynja jingialang ban pynioh ia ka jingshitrhem “Ka Jingiatylli Ki Khun U Hynniewtrep” ha kano-kano ka kam kaba kthah ia ka iap ka im. Lane shim ia ka jingrwai Phareng “Ramona” bad buh da ka dur (ktien) kumne :-

Lanosha,

Ki por b’la leit kin wan pat

Lanosha,

Phin wan ummat jong nga kin rngat

Sa tang ha jingphohsniew

Ia dur bhabriew jong phi nang i,

Ban da don ki thapniang

Sha kut pyrthei nga ruh ngan jngi

Lanosha,

Ki lum ba jrong kin hiar madan

Lanosha,

Phin wan ia nga nangne ban tan

Sha Ri ba suk ban im bad phi baroh shirta

Lanosha – iathuh seh – ia nga.

(Webster Davies Jyrwa)

Ynda phi la rwai ia katei ka jingrwai phin shem ba ka dur bad ka sur ki iahap bad u nongrwai u lah ban rwai da ka jingshem mynsiem bad kata ka ‘expression’ ba nga la thoh shakhmat.

Ki don bun ki jingrwai Phareng kiba la pynkylla Khasi ba la rwai ha ka ktien Khasi ha kito ki por hadien ka Thma Bah hynrei ym lah kynmaw shuh ia ki. Kiba dang kynmaw malu mala ki long – “ When Whip poorwhils Call” ba la pynkylla –

Ha la i ïingtrep ba kynjah marwei,

Duitara kynud sngewsynei.

Ki khla ki dngiem ki kitbru bad ki ñiangkynjah

Sawdong i ïingtrep ki wan kynoi thiah.

U Bah Windronel u nang bha ban rwai biria, haba u kylla Khasi ia ki jingrwai Phareng u rwai –

Nga wan hynnin na Sohra

Nga wan kit u slap bad u phria.

I thei kup’ nup-bah ha u slap i shah

Ban peit tang khohwah i iapngiah.

Kawei kaba nga iohi ha ki jingrwai kiba don ha KA MARYNTHING RUPA ka long-

- Ka jingpynroi ia ka ktien Khasi da kaba pynrung ia ki ktien bad kyntien na kylleng ka Ri, kum Shirup-Shiliang, Kuku ne Titpu, Kynmaw (Kynmo) Tympang. Kane ka la long ka jingpyrshang jong i Bah Gilbert bad jong kiwei-kiwei de ki nongthoh kot Khasi ban iarap ban pynroi bad pynphuh pynphieng ia ka ktien khasi, kata da kaba shim ia ki ktien bad kyntien kiba iahap sbiak ha ka rukom ia kren ha ki thaiñ bapher bapher. Hapoh ka Bri U Hynñiewtrep, Talawiar U Sohpet Bneng la na thaiñ Khynriam ne thaiñ Pnar, thaiñ Bhoi ne thaiñ War. Peit ia ka jingmut jong ka ktien ‘Shirup’ –

Shirup u ialai

La Kam ki shipai,

U miat i muluk i pyrthai.

Ka ktien Kynmaw Tympang ka sngewtynnad hynrei kham sngewshngiam lada buh Kynmo Tympang : kumjuh ruh ha Tre Riat ban ha Trai Riat.

- Ka jingpynwan biang ia ki ‘ktien Kylla kiba ngi ju ia mlien ban kren ha ki por mynshuwa ka pynsngewtynnad ia ka jingpule kum –

Ynnai lengtynneh, ynnai litshongsheh,

Likhaseh, ynnai leng phareh.

(Jingrwai No.12 – na ka kot ka marynthing rupa.)

“KING MORNUD” ia phi lang baroh

(Jingrwai No.51 – na ka kot ka marynthing rupa.)

Kum ban shu pynkynmaw hangne, u Babu Soso Tham ruh ha poitry – Ki Sngi Barim U Hynñiewtrep u buh ia kum kine ki ktien kylla –

“Bor ha la, snoh ha piew”.

- Ka jingbuh ia ki kyrteng shnong kiba pher ba pher kiba don ha kylleng ka Ri, kum Jaliakhola, Maheskhola, Mawlat, Shiliang Myntang, Tuber, Lapalang, Sohmynting, Mawsynram, Dawki, Majai bad kiwei-kiwei, ka pynpaw ia ka jinglah bad jingtip kaba kham bha jong i bah Gilbert shaphang la ka Ri.

- Ka jingbuh ia ki lum ki wah, ki kshaid ki krem ba pawnam bad ki pung ba itynnad ha ka Ri jongngi, ba ki lawei kin tip, ioh ba kine ki jah ha ka jingkylla ki jingpynlong kum U Lum Sohpetbneng, Lum Diengïei, Kshaid Nohkalikai, Wah Myntdu, Wah Umngi, bad kum ka pung Thadlaskeiñ ba la tih u Sajar Nangli bad ka kynhun ki khla ka wait jong u da ki tdong ryntieh. Kumjuh ruh kum ka Nanpolok ba la shna da u Polok Engineer ha ka por u Sahep Ward.

Ha ka jingrwai No 67, i Bah Gilbert i iathuh shaphang ka Iew Mawngap kaba la long ka Iew Khasi dei phan kaba heh tam ha kine ki thaiñ. Naduh surok bah haduh ba lait ka surok shnong, ki ieng ki ïing buh phan bad ki pylla ramhah. Ki briew na ki thaiñ sepngi ki wan kit phan da ki kulai. Ki thep ia u phan ha ki byrni ba la sdien ar liang ia u kulai bad ki kit ha la met. Da ki spah ki kulai ki wan kit phan man ka sngi ha ki por phan. Ynda ki leit phai pat sha la shnong ki shong da ki kulai kit phan ba la siang jin da ki byrni ; ki shynrang kumjuh, ki kynthei ruh bad ki pynmareh kum ki “Cowboy” bad “Cowgirl”.

- Ka jingbatai ia ka Kolshor U Khasi, kum na ka liang ka iadei kur iadei kha, ka kynjoh khaskaiñ haba kiew ïing thymmai, ka jer khun, nguh meikha bad kumta ter-ter. Nangta sa ki jaid jhur bad jingbam trai ri, kum u Jamyrdoh, Jalynniar, Jangew, Jathang. Nangta ka Ja Sohriew ka ja Phandieng. Haba kren shaphang ka doh-tir na Mawkyrwat, ka pynkynmaw, ba ha ki por mynshwa ki die dohsniang, khamtam ka doh ba shu tir bad ba la shet thai ha Iew Mawkyrwat bad kumjuh ruh ha Mawsynram. Lah ban bam bad tah mluh sohmynken lada khlaiñ ki bniat bad khlaiñ ka nierbah.

Ki jingrwai ha KA MARYNTHING RUPA, ym tang ba ki pynsngewtynnad ia ki nongpule ne nongrwai hynrei ki iarap ban tip shaphang la ka jong ka Ri ba nga ieit ; KA RI UMSNAM U KÑI U KPA. Nga sngewburom ia i Bah Gilbert ba i la pynkynmaw biang ia ngi kiba bun ki ‘riew rim ia ki por ba la leit – KI SNGI KA AIOM KSIAR, bad ba la bsuh shibun ki jingtip ia la ka Ri da ki ktien bad kyntien ba don ha ki jingrwai. Nga kyrmen ba i Bah L.Gilbert Shullai in nang lum bad thoh shuh ki kot kiba lah ban pynroi ia ka Culture KA KOLSHOR U KHASI.

Webster Davies Jyrwa,

Retired Senior Station Director,

All India Radio

and

Member, Plan Projects Committee,

National Academy of Arts,

New Delhi.

Dated Jaiaw Langsning,

Shillong

The 15th October 1984.

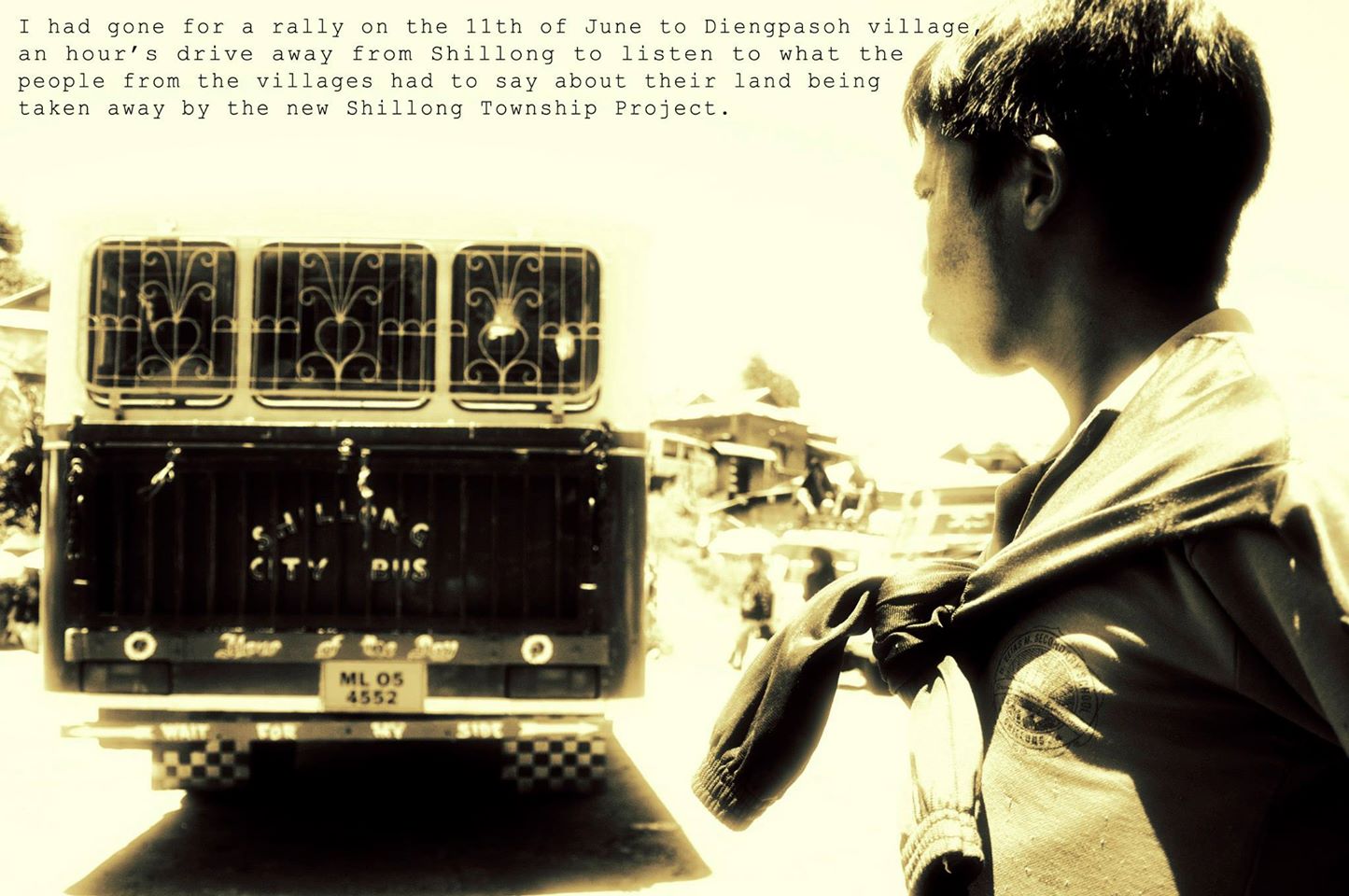

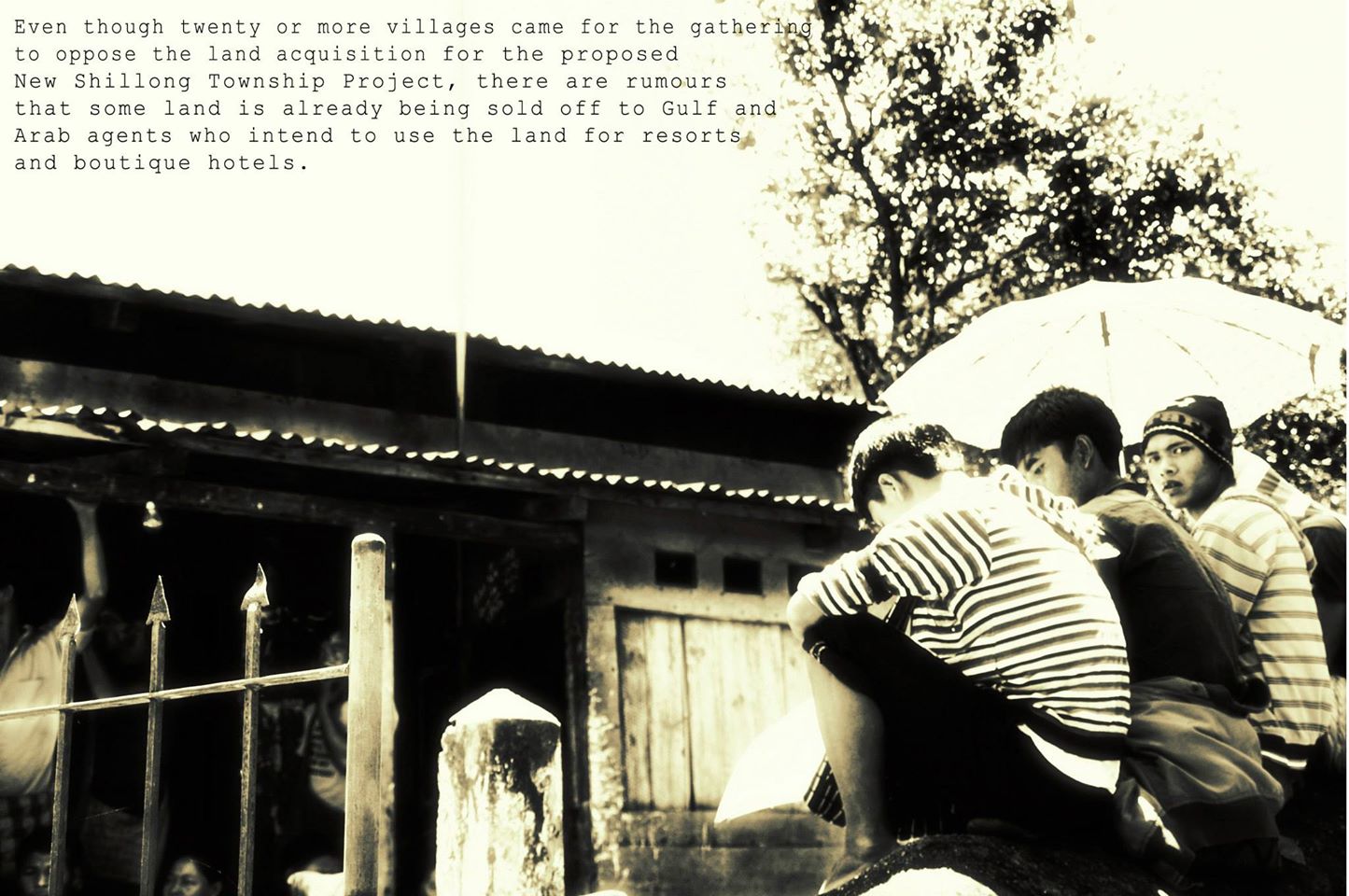

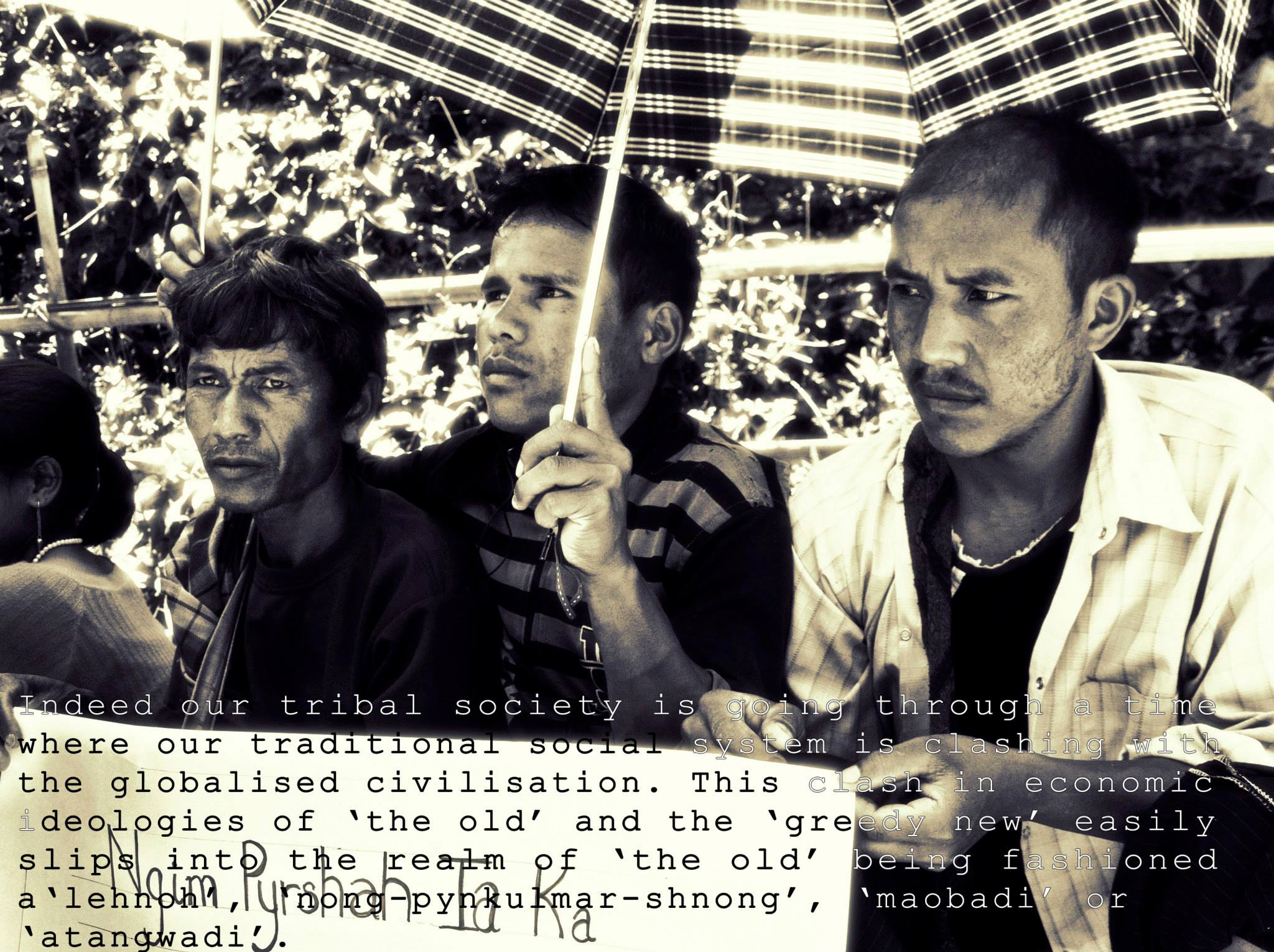

Protest & Survive – a photo essay

On the outskirts of Old Shillong – simmering anger. Farmers, who have turned these areas into fertile zones of agriculture, see themselves being displaced by concrete structures and real estate speculators. New Shillong Township is being sold as a solution to the congested Shillong, but the plans have revealed that NST would be a network of gated communities of the rich indigenous elites and outsider speculators looking towards constructing a post modern Hill retreat.

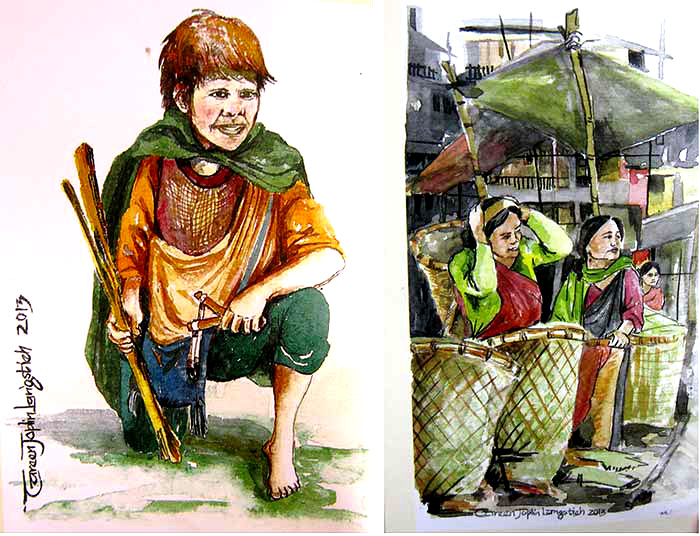

Wanphrang Diengdoh, a member of Thma U Rangli Juki (TUR) documented one such protest against NST which was held at Diengpasoh. Click any picture to enter the Gallery.

Are Khasis headed for cultural genocide?

I remember a time back when I was in Catholic school; I was speaking in my mother’s language, Khasi during break time. A teacher walked in and overheard, scolded me and told me to speak only in English. The school diary even had a rule enforcing a ban on speaking any language other than English. I didn’t realize it at the time but I was a victim of ethnocide or cultural genocide.

Ethnocide or Cultural Genocide is a term that was coined by Rapheal Lemkin in the 1940’s. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) defined it as “Ethnocide means that an ethnic group is denied the right to enjoy, develop and transmit its own culture and its own language, whether collectively or individually. This involves an extreme form of massive violation of human rights and, in particular, the right of ethnic groups to respect their cultural identity.” The French ethnologist Robert Jaulin proposed a re-definition of the concept of ethnocide in 1970, to refer not to the means but the ends that define ethnocide. Accordingly, ethnocide would entail the systematic destruction of the thought and the way of life of people(s), different from those who carry out this enterprise of destruction.

Luckily for me the teachers in my school were lax in their enforcement of that rule and we had classes which taught us our language and culture adequately. Benefits of high-priced education, I suppose. I learnt enough of my mother’s culture and traditions to be aware and rouse interest.

Recently in college, one of the lecturers, a non-tribal Catholic priest on finding out that I was an atheist tried to get into a debate with me. He tried to use the argument that all human cultures has a sense of innate “goodness” or “Christian-ness” and that proved the existence of God. He went on to give the example of Khasi religion. He might have gotten away with this if it weren’t for the fact that he was dealing with a History student. I politely pointed out the fact that Khasis are believed to have performed Human Sacrifices; the Kamakhya Temple in Guwahati is believed to have been built on the site where the Khasi tribe once performed these sacrifices, before they were driven out of the Brahmaputra Valley by other tribes. I asked him how this was similar to his Judeo-Christian beliefs.

I then mentioned the “Thlen” and “Nongshohnoh” mythology and the supposed prevalence of Human Sacrifice in some sections of Khasi culture in order to gain material wealth in older times. At first he was dazed and confused; clearly he was not knowledgeable of Khasi history but he went on to say that those were ancient times and continued to evangelize to me. Basically he was trying to lecture me on my own culture and to give me a garbled and white-washed version of it. This is a form of Cultural Genocide or ethnocide. In another instance, he was holding a lecture on dress codes for an upcoming school program and he went on to say with a certain smug satisfaction borne of ignorance, “Tribals from North East India are known for dressing modestly.” I interrupted him and told him that he was no authority to decide that and that he could not possibly know about the dresses of all the tribes and ethnic groups of North East India and duly supplied him with the example of “traditionally” scantily-dressed Naga dancers. He became defensive and went on to say that he didn’t mean anything by it.

I myself didn’t think much of these incidents until recently. But I now realize that this was an attempt at Cultural Genocide or Ethnocide by outside forces, though I doubt there was any malevolent intent to it. They simply expected our culture to match the “Noble Savage” stereotype which clashes against harsh brutal reality. But even if their intent was not malevolent they are nonetheless harmful. I saw this firsthand when on one occasion I witnessed a Christian sermon to rural folk by a South Indian priest, he went on to try to explain their own culture and religion to them with much white-washing and Christianization, but none of the rural individuals stood up to correct him. This is possibly because they have little or no knowledge of their own history. I can imagine this happens often in rural areas, especially where education is dominated by Missionaries, who teach a misrepresented and Colonial version of Khasi history, which is not only untruthful but insulting to the Khasi culture.

I don’t advocate that the Khasi people return to a past where in they went hunting and sacrificing human beings but the people should be educated and well-versed in our old beliefs and practices to present an opposing view to the Judeo-Christian narrative. Only in such an environment can critical thinking and actual pride in one’s culture happen. The Khasis of Meghalaya are lucky in some ways due to the survival of Khasi political institutions and the fact that much of Khasi culture is preserved in books and is widely taught to those who opt for it in the major educational institutions of the state. The Missionaries weren’t an entirely destructive influence either, particularly the Welsh Missionary Thomas Jones, as they provided the Khasi people with means of education and a written script to preserve their culture. The Indian Republic itself has provided means and methods for the protection and preservation of our culture. But the preservation of Khasi culture and history is a continuing battle that must be carried out for the greater good of the people.

Bibliography:

- Noble Savage- http://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Noble_savage

- Kamakhya Temple- http://www.durga-puja.org/kamakhya-temple.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamakhya_Temple#cite_note-31 - Cultural Genocide – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_genocide

- Ethnocide- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnocide

- The Khasis by P.R.T. Gurdon

Five poems by U Soso Tham

U Soso Tham was born in Sohra (Cherrapunjee), Meghalaya, in 1873. He served as one of the first school teachers of Khasi at Government Boys’ High School, Shillong. He started writing very late in life and published two collections of poetry besides translated works. From such humble beginnings he rose to become the uncrowned though acknowledged poet laureate of the Khasis, whose poems are sung and whose words can still be heard everywhere. He died in 1940.

Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih’s English translations of Soso Tham’s poems eschew the literal, in favour of the poetic. He brings onto the translations his deeply bilingual world to create a definitive version of U Soso Tham

The Green Grass

Quietly in the wood,

It grows among the weeds;

An uncommon blossom, u tiew dohmaw,

A thing of lofty thoughts.

Quietly by shadowy streams,

To be fragrance when faded,

The joy-giving fern

Remains green for twelve moons.

Tell me twilight, beloved of the gods,

And you the motley clouds;

Tell me where is that star

That first speckles the sky.

Quietly he lives, quietly he dies,

Amidst the wilderness;

Quietly in the grave let him rest,

Beneath the green, green grass.

U tiew dohmaw: a wild flower, symbol of great wisdom.

≈§≈

The Days that Are Gone

I will go to ri Sohra to be among the hills,

The land of u tiew sohkhah and u tiew pawang lum;

The land of ka sim pieng, the land of u kaitor,

The land of valour, the land of culture.

Listen, in ri Sohra, that ïewbah has arrived,

It resonates the cheering that the archery may be won!

It sinks into the caverns, from the sky too it creeps,

To a Khasi, a Pnar, a Bhoi, or a War.

Its cliff-edges too overflow without end,

With the torrent that roars, the breeze that’s tender;

And the heart that’s forever youthful hums in the woods,

Thus rumble the gorges of ri War and reverberate the boulders.

Long have I departed from relations and friends,

Though others have gone, others linger on;

Thus the honour of Sohra and its silver seas,

Once more, once more, came dazzling to me.

Thus the days that are gone, they surge and they surge,

I don’t know the beginning or where they would end;

Only this I do know, that often I do want –

Once more, once more to be a child.

_______

Ri: country

U tiew sohkha and u tiew pawang lum : orchids

Ka sim pieng and u kaitor: songbirds

Ïewbah: big market day

Pnar, Bhoi, and War: names of the Khasi sub-tribes as well as linguistic and geographic description.

≈§≈

The Cipher on the Stone

When still in my father’s and mother’s laps,

Though I survived on the herbs, the world yet was flat;

I bragged, I scorned, I daydreamed as a child;

I laughed, I cackled, to be good I could not.

When the river clamoured that it boiled without stop;

When I watched the grass that was green;

Like a hip-hopping bird inspecting itself, I enquired:

“Tell me o death, where do you live?”

Like a sturdy fruit tree that unfurled its branches,

When seasoned, and the thoughts had broadened;

That daydream later came to be seen,

As one of the ciphers etched on the stone.

The grass is now tanned that the river has ebbed,

It is then that I see— a mysterious Something that it comes;

The tongue is now tied and I cannot open my mouth,

Sunken in deep thought that winter has arrived.

≈§≈

The Golden Grains

Enlightenment we seek around the world;

That of the Land’s we know but nought—

How in ancient times the Uncles the Fathers

Had fashioned politics, had founded states—

When all the race, u Hynñiew Skum

Had lived apart— within the gloom.

Amidst the Stars, the Sun, the Moon,

On Hills, in Woods the Unknown roamed;

Man and Beast, Tiger and Thlen,

Then they spoke one only tongue;

Before the demons and the fiends emerged,

Then they worshipped one only God.

The Word of Man still had its worth,

They let the Phreit feed on their fields;

Morning and night they laboured hard;

In the Belly they stuffed their Paperback;

Then they bred their Fairytales,

Then out they came the Fables.

Many a Parable they then described;

“From Here,” they said, U Thlen emerged;”

“Evil and Sacrilege, from where had flooded?”

“From Here,” they said, “from Diengïei Mount:”

The other one they knew around,

Why they had called, “U Sohpet Bneng.”

About their God, Evil, Virtue,

Thus in parables they spoke:

Their Likenesses too, they said of old,

Were draped before Man as if by Charm:

In the bowers of Stars some still remain,

Others into entangled jungles have sunken.

“To bear the Sin, to shoulder all,

from the Cave of the Sanctified Leaf,

The Sacrificial Rooster,” they said, “came standing tall,”

For “God to be caretaker of the covenant from above:”

They organised a Religion forever upheld

The Children of U Hynñiew Trep.

When a mother mourned heartrendingly,

Trailing her son’s bier tearfully;

They played a dirge— telling the tale

Of Lapalang, a Deer of legendary fame:

How it mounted the Rusty Arrow,

How the bitter tears began to flow.

The Indications on the stones

Are weed-covered in hills and woods;

The Honourable the Learned

Here they speak in different ways;

From hills, within the shade

The stone, the wood would speak the human tongue.

The ancient tribe— Khasi and Pnar—

A Multitude that spread throughout the World:

The hidden Light— that we may quest,

Scattered in Huts throughout the land:

From there intelligence to illumine,

The Olden Days of Ancient Times.

Enlightenment we seek around the world;

That of the Land’s we care but nought:

As others the days will come,

The ancient Light that we may learn:

The Root the Seed of living Light,

It sinks into Primordial Days.

The Cerulean Rock will soon emerge,

When it stops u Lapmynsaw!

The layering Cloud will disappear,

When the Rainbow comes to life:

Pour forth your colours, O Gilded Pen

Let the man in darkness comprehend.

______________

U Hynñiew Skum: another name for u Hynñiew Trep, ancestors of the Khasis

Thlen: legendary man-eating serpent, symbol of evil

Diengïei: the mythic Tree of Gloom, marking the end of the Golden Age and the emergence of evil. It stands opposed to U Sohpet Bneng, Heaven’s Navel, a symbol of the intimacy between man and God. The tree was felled by the help of a little wren called Phreit in exchange for paddy from the fields

Cave of the Sanctified Leaf: parable of the Second Darkness and how the rooster had sacrificed his life to persuade the sun to return to earth from the sanctuary to which she had fled

Lapalang: legend of Lapalang the Stag and how he was hunted down by the Khasis. The mourning of Lapalang’s mother had given rise to the first Khasi funeral dirge

Lapmynsaw: sun-shower, bearer of danger.

≈§≈

Fortitude

Dew drops on the grass,

In the morning they glitter;

I too from home will depart

To hunt for these pearls.

From the grass that is green

They take off with the sun;

Like them then I’ll plunge

To an unknown region.

The thorns though they prick

In a faraway street;

From home I’ll depart

And return long after.

The heart too will grieve

Alone faraway;

The tears that gather

Are actually pearls.

Maram Sahbiej from Wahrit

Every winter vacation we’d go to Wahrit.

It was a thriving village where I once burnt the village market after I had quenched my boyish craving for a ‘Ma-kyllain.

The winter holidays were too short for a full village adventure and the mischievous deeds were continued in small episodes stretched (out) through many winters.

Here in Mawlai I am clad in the infamous garb of a Maram.

“Go back to your Wild West Khasi Hills, you son of a maram”, the customary reprimand of my father’s kin, the original inhabitants of Mawlai.

This place is not my own.

Those who love me call me a ‘sahbiej’ and those who feel threatened, by my poor presence, suspect my love.

The truth is, 39 years of living in Mawlai has made me a pucca maram.

I will never be able to return to the market.

My burning desire left no ashes

For the hill where the market once stood now shoulders the Government’s unhealthy health center and my playground is now a parking lot for the marwari’s dalals.

My people pray that they may fall sick only on a Friday.

The wise Doctor from civilized Shillong comes on a Friday only.

Do they miss my grandfather, a quack, an ignorant man who showed them patience, and the ‘Tiew Lily in his garden when they broke a leg?

A pacifist in church matters but a disciple of the Khasi world view,

He was always there for them.

May God give me the strength to return to my own place, poor and violent and sickly it may be.

May my dead forefathers plead for my case – a dwelling in my own remote, savage place.

—⊕—

NOTES

Maram: resident of West Khasi Hills District of Meghalaya. Owing to the backwardness of the district, the word Maram has been used derogatorily to mean an individual from the West Khasi Hills who is socially backward and therefore a savage rustic.

Mawlai : A locality of Shillong considered a rustic outpost by the Shillong elite

Sahbiej: a distortion of the word ‘savage’. Within the context of the poem ‘Sah’ means to remain stagnant without progress and ‘biej’ means fool or foolish or backward.

Makyllain: a kind of cigarette prepared by the smoker himself using a particular paper and finely chopped tobacco. This is quite popular among the people of West Khasi Hills since it is cheap and easily prepared. The word Makyllain is now used to describe a rustic from West Khasi Hills.

‘Tiew: short for Syntiew meaning flower. The ‘Tiew Lily is usually used by practitioners of herbal medicine to help people when they break a leg or bone.

Games Khasis play

Text by Avner Pariat

In the early part of 2015 (April 30th) Khyndailad Film Club (KFC-Shillong), with financial assistance from the Directorate of Sports and Youth Affairs, Government of Meghalaya, conducted a cultural ‘experiment’ at Pahambir, Ri-Bhoi district. INDIGIGAMES 2015 was a one-of-a-kind attempt at re-living and, crucially, re-imagining the old past-times that were once enjoyed in the Khasi-Jaintia Hills. Football, cricket and others have essentially displaced the older sports/games which were customarily played by a large number of people, especially in the rural areas. Taking a cue from similar events throughout the country and the region, KFC Shillong developed a plan for reviving – without ‘jingoism’ – the much loved but forgotten “indigenous” games of Ri Bhoi district.

In a novel way, INDIGIGAMES 2015 celebrated value and beauty of their old “arts”. In the old days, many of the games, were never just “child’s play” but actual training for combat and physical endurance. By highlighting them, it is hoped that more people would once again start participating in and sustaining an interest in these forms. While it was not given the big budget money or publicity like other “indigenous” festivals, INDIGIGAMES 2015 managed to do something more important – bringing together the local village communities and having some fun in the sun!

Khalai

This game has various versions. Sometimes pebbles, cowries, or small bric-brac are used instead of sticks. It involves tossing the sticks up in the air and catching a stipulated number using the same hand. The winner is the one who manages to grasp the correct number of sticks each time.

Khloisynrei

This game is a variant of tug’ o war. However, instead of using rope, a stout piece of bamboo is used. The participants sit down on a large mat and when the signal is given, each must try to pull the other up and over. The winner is the one who drags his/her opponent onto his/her side of the mat.

Kyllasohprah

This game/exercise tests upper body and abdominal strength. Participants have to grasp a crossbeam firmly, lift themselves off the ground and bring their feet up and in between their arms. They have to repeat this as many times as possibly without letting their feet re-touch the ground. The winner is the one who does the most number of turns.

Latom

Known by many names, in various parts of the world, pom latom or spinning top fights were a common sight in the neighbourhoods. The winner is the one who manages to ‘kick’ the others out of the circle (or, cruelly, destroys all the other tops!)

Mawpoin

Once very popular with local children, this game holds a special place in the hearts of many adults. It is basically like ‘dodgeball’ but with the added difficulty of having to raise up a “pyramid” of stones (in this case planks) whilst running from the opponents. This is a lovely mixed-sex team-emphatic sport; a person is considered ‘out’ if he/she is hit on anywhere but the head though rules might differ. The winner is the team that manages to raise the pyramid and gets all the opposing team members ‘out’ as well. This game must surely be introduced into schools and colleges!

Rongmaw

This game is a sprint/dash event but with the added condition that one needs to bring back a small stone from the opposite end of the field. This continues, back and forth, until all the stones from one end have been deposited at the starting point. It tests not only speed but endurance as well.

Sitnup

This game was a popular past-time among the cattle herders of Ri Bhoi. It is a rather complicated game associated deeply with the folklore of the area. It is played using nup, large seeds that are found in a certain jungle tree pod. It is similar to the ‘shooting’ games played with round marbles but has certain conditions which have to be fulfilled such as using certain parts of the body to fling the nup forward. The winner is the one who fulfills all conditions and is able to ‘shoot’ his rivals’ seeds down as well.

Marehdiengdang

Don’t be bamboozled by the name. Here’s a more familiar game – a sprint but on stilts!

Triathlon

We named this event the “triathlon” (for lack of a better word) because it comprises three separate games put together. The first game is a puzzle – kyrwoh – which needs to be unlocked before a participant can proceed to the next stage. The second obstacle an opponent must overcome is a reaching the top of a greased bamboo pole. Finally, they have to strike a straw target once with arrows fired from a bamboo crossbow. The winner is the one who completes all three events in the least amount of time.

Bah Rani Maring, a local farmer and artisan from Pahambir, built and equipped all the “gear” (games and otherwise) for INDIGIGAMES 2015. He makes everything almost exclusively with bamboo, these include the spinning toys and swing sets. In addition, he also crafts a number of musical instruments like the bom (drum) and duitara (stringed instrument)

Some questions for us Khasis

No identity or ethnicity exists without history. No history remains cast in stone. Wanphrang Diengdoh, musician and filmmaker from Shillong asks 5 questions about Khasi identity and if you feel like responding to Wanphrang Diengdoh’s questions, feel free to comment or send us your response at raiotwebzine@gmail.com

- The Sohra dialect which is now the lingua franca of the state owes its genesis to the Welsh missionary Thomas Jones. For the Khasi nationalist (not of the Seng Khasi kind) this position is acceptable. Why? Perhaps because we are happy to recognise that we owe our identity to a European, a doh-lieh and therefore have no problem internalising Welsh anthems as our own? What would the implications be today if the Bengali, Krishna Chandra Pal in 1813 managed to evangelise more Khasis than the Welsh did eventually? Would we have embraced some other script as ours? Would the fate of the dkhars have been different in 1979, 1987 and the other years that had outbursts of communal violence?

- For the followers of the so-called niam Khasi or Khasi traditional faith, the claim that the niam Khasi had no flirtations with other religious ideologies makes me thoroughly uncomfortable. To make matters a little bit more complex, Nilmani Chakravarty, in Atmajibansmriti, (Calcutta, Bangabda 1827) records, “Among the early Khasi gentlemen who were attracted towards the Brahmo faith, mention be made of Job Solomon and Radhan Singh…This Mawkhar Brahmo Samaj Mandir was the first community prayer hall established at the initiative of the local Khasi Brahmo converts of the Hills…Here they met every Saturday for Brahmo prayers…Radhan Singh jointly translated some Brahmo prayers into Khasi language”. Also, the son of the duibhashya, Jeebon Roy Mairom, Sib Charan Roy Dkhar translated the Bhagavad Gita along with other books on Khasi religion including “Kot Tohkit Tirtir shaphang ka niam tip Blei ki Khasi”, “Ka Niam Khasi –Ka Niam tip-blei tip briew” and “Ka Jingiakren iapule shaphang ka niam”. Most of these books are still published today thanks to the first printing press of Meghalaya, the Ri Khasi Press in 1896. This was established by Jeebon Roy who was also one of the founding members of the Seng Khasi organisation and also worked as the Extra Assistant Commisioner. He eventually resigned and got involved in the lucrative limestone mining. Radhon Singh Kharsuka’s, ‘Ka Niam Khasi’ is also still widely circulated.

- Should the Seng Khasi in 1899 have originated from a position that aimed to secure the economic development of the Khasis and not just to institutionalise their dance and rituals and claim custodian position, then this movement, which is perhaps the greatest cultural movement the Khasis have ever had, would have also taken a stronger stance against the devastation of our resources and environment by outside forces – namely large corporations and the state that justifies its actions in the name of development. But perhaps this position was not possible because some of the pioneers of the Seng Khasi were also well-to-do government officials. Today, I wonder which custodian of Khasi political, cultural and religious identity would take a stance against uranium mining, deforestation or the decline of traditional laws; the crony feudal and capitalistic model that now enslaves our Khasi brethren. Or even more culturally radical, develop a ‘new’ script for the Khasi language. Instead, what we see are religious practices slipping more into the realm of a spectacle masquerading as authenticity; an authentic spiritual purity which is made even more complex by the formation of the State of Meghalaya.

- Neither religion nor language can be used to assert a sense of purity. Are you more Khasi than your Khasi Christian or Khasi Muslim neighbour? Are you more Khasi because you speak the Sohra dialect? Are you more Khasi because you choose the jainsem over jeans (Even though the jainsem origin can also be contested)? By the same logic, my Khasi Muslim friends could also apply for a minority within a minority status as well.

- The question now is, if one claims to be a ‘pure Khasi’ (with traditional systems of administration, governance and rule of land in place) is there room for this ‘pure Khasi’ in the nation state? I do not claim to come from or to be aiming for a point of nothingness where we are all the same – a post modernist comfortable sofa – but rather to want us to question ourselves and accept the fact that we are different yet have areas of commonality that we should further investigate, as opposed to dangerously parading them as political and or religious differences that fuel animosity. The time is well overdue for us to shake up a few feudal coops, so that the problems of our everyday existence will not be simply palmed off to the refugee from across the border.

On Khasi identity crisis

Just a few days ago we published a piece by Wanphrang Diengdoh on questions for Khasi identity. We knew that there would be others who would join the discussion. Bah Don Tmain, an online persona representing a group of self styled thinkers and artists of similar tastes, lifestyle, ideas, views… and shyness try to problematise Wanphrang’s questions and also queer up the pitch about the way certain knowledge of Khasi worldview suffers from its epistemological distance from its query.

So much questions has been asked and pondered upon by the caring few about the Khasi culture and ka niam tre and I can’t stop but join in the collective concern that we are heading somewhat into a maelstrom of identity crisis. Also a lot of resourceful individuals had come in and help clarify the queries of self reflection through social actions, extravagant and otherwise, but ended up disappointing a certain half of the populace while appeasing the other. The debates hence resulted rave on perpetually.

First, why is there a need to define religion? if the Khasis had their own, why do we need to compare ours to the others in order to quench our human lust for ruthless comparing and categorising? Then again most people would most probably hold the phrase say ‘unity in diversity’ in high regard. If we are to live in unity despite diversity I think we should let go off our fetish for labelling. Only Lazy people do.

I may not define our religion here in this piece, but I will attempt to clarify certain points as to how shall we answer, ‘Kaei ka Niam Tynrai?’ My indulgence in street talks and countryside chats with the ritual practitioners of the faith has led me to conclude that the Khasi religion or the believers takes the ontological value of every object (both the physical and the meta) in the cosmos with predominantly great importance. A true niam tre believer would not obviously even consider comparing his religion and philosophy to other’s. To him, everything has an ontological purpose or value, so does Ka Niam Tre.

So to define our own religion through the western eyes and not our own is to defeat its very essential philosophy. More like answering the door from outside the house. An ideal stance to be taken to define ka niam tynrai is to go deeper inside and stand at the core of its being, if one must.

Certain writings had popped up here and there inscribing inferences of a kind. They seem to convey that there is a need to have a mediator between the creator and the followers in order for a certain faith to be classified a religion. Bah Mohrmen, amongst others, also hints at such things in a recent essay (ST, Jan 25/16). It is somewhat contradicting to unfold the tapestry of ka niam tre with a christian ideologically-charged yardstick. Plus, there is no social consensus that says defining religion is important.

Then there are cries for a change as opposed by cries to conserve our culture. we had always been living in the median spot between the two. Change is inevitable. With change, a culture evolves. The question to be asked is: Should this evolution be guided by a few dominant minds? or should it be let to go how it is supposed to go, naturally, with a promise of a gradual acceptance by all?

To conclude my first piece at www.raiot.in, What I normally do at home is not tradition in a traditional sense. But then isn’t tradition a legitimate child of repetition? Who’s to say what among our daily social routine qualifies to be part of our tradition and what doesn’t?

The Khasis as Hindus

Perhaps this article is ill-timed. Perhaps in the current scenario with various Far Right groups actively seeking a Hindutva agenda it is not the best time to be writing things which they could use for their own benefit. This is particularly true after the recent maiden procession carried out by the RSS in Shillong which has evoked so much reaction. However, these events cannot forestall the need for articulation. It waits for no one. With this in the background, I would like to present an argument that has been brooding in my head for a while now.

I have often heard it repeated over and over again especially by the Christian clergy and its fraternity that Khasis were/are not Hindus. They often say, in a very vague language, that essentially we worshipped One God (U Nongbuh U Nongthaw) through His “ambassadors” here on Earth. So in a sense ‘Lei Shyllong and other ancient deities might be suitably placed within a pre-Christian monotheism. This seems contradictory in more than one way. The most obvious is that it seems the Khasis are the only ones who profess this. Other tribes around us who have undoubtedly influenced and been influenced by the Khasis worship multiple gods not a God – these are full framed figures, resplendent in their distinct tribal garb, not simply allusions to a one Universal. This aspect is something we need to interrogate further because this pre-Christian “Christianity (monotheism)” appears to be revisionist. The frequency of the articulation of this idea among the Christians – especially Catholic priests – seems to betray its origins and motives. After all, it is much easier to convert people by drawing comparisons to that which they are already acquainted with: that the introduction of new gods is in reality just a change in nomenclature and ritual, that essentially they have always been worshipping the same God.

I am personally interested in the fact if the Khasis claim to be a matrilineal culture/society, why is U Nongbuh Nongthaw (The Keeper/ Creator) a male deity? Shouldn’t ‘he’ be a ‘she’? I realize that this is not necessarily an air-tight hypothesis but humour me. The Pnars and Bhois, interestingly, seem to place more importance on female divinities – the goddess Riang Khangnoh, goddess Myntdu, goddess Lukhmi are far more popular than any male counterparts. And they are not simply goddesses of the homestead either, they can wonder outside from spring to spring, blessing the families that stay along their path, they can serve as guardians (‘lei khyrdop) protecting Jowai like Myntdu does and they can also guarantee a good harvest like Lukhmi. They seem to have more character, more nuance than the Nongbuh Nongthaw. To simplify the pre-Christian era has been one of the major projects of the missionaries of various faiths. These include the Christians and the Hindus as well. Both have, in their own manner, drawn attention away from the differences and harped on the similarities that were allegedly shared. The Christians have been vague about it while the Hindus have embraced the ‘nitty gritties’ of the idiosyncratic Khasi myth pantheon as their own.

When we talk of Hinduism we have been warned time and again about the dangers of ‘centralizing’ it: that there are, in fact, many Hinduisms. This is a convenient starting point for interrogating the Hindu processes that went on in the Khasi and Jaintia Hills before the coming of Christianity. To simply state and defend the “Khasis were not Hindus” tenet with no evidence except popular belief is bad science. On the contrary, there is substantial material evidence to support the claim that they were, indeed, Hindus. In Syndai, you will find a large Ganesha sculpture – among others – of some age carved into a large rock; the local people call it ‘U Khmi’ (interestingly the word means “earthquake” in Pnar). Dawki has a number of old rock carvings which seem to be influenced by Hindu traditions. Legend has it that the Kamakhya Temple in Assam was originally a sacred Khasi site – a point acknowledged by temple management in publications – where a type of mother goddess supposedly resided. She was called “Ka Mei Kha” by the Khasis, which over time morphed into Kamakhya. The phonological shift is noteworthy. Nartiang and Iale Falls were important locations for Shakti human sacrifices. The former is still an important shrine for pilgrims to visit. Mahadek, also known as Laittyra, was called that because of the presence of a Mahadev temple within the village. Mawsynram still draws a decent number of Hindu pilgrims who suffer the horrible roads in order to perform puja at the mawjymbuin cave, which they consider to be a shiv-ling. Interestingly, these sites are all near borders – either with Assam or Bangladesh. There are undoubtedly other similar sites and shrines throughout these hills and valleys which await re-discovery.

Beyond the ostensible spaces, there are also a number of cultural borrowings that seem to have been directly influenced by Hinduism. This should not surprise (nor anger) us. The North East is basically a land bridge (possibly one of the most important in history). Materials, skills, ideas have flowed through this region for a very long time from East to West and vice versa. The fairly recent isolationism and the subsequent xenophobia should not fool us into believing otherwise. Many important festivals like Behdeinkhlam, Lukhmi have strong links with larger Vedic currents. The references to Lukhmi/Lukhimai are quite clearly to a ‘tribalised’ Lakshmi. During Behdeinkhlam, the rot (tower-like structures made of wood, bamboo) must be cast away after the religious festivities are over. This is interesting because the worship of the (non-Classical) Hindu deity Jagannath (Odisha mostly) also involves similar structures which are called rath (chariot). Note the similar names. The casting away of the rot is akin to the casting away of the idols at Durga Puja after their roles as ‘cleansers’ have been fulfilled. Even the ritualistic animal sacrifices at Shad Pomblang might be re-seen in the light of other festivals like Gadhimai, Bali Jatra and others. When I was to be married, there was some discussion about putting up banana stalks in front of the entry way which is a very common Hindu practice – this in spite of the fact that my in-laws’ household is almost exclusively Christian. This ultimately did not happen but it was interesting nonetheless.

As I had mentioned earlier, this piece might be misconstrued for obvious political purposes. I am not interested in privileging the mainstream Hindu tradition over the ‘smaller’ traditions. Further, I hope the reader does not think that I am attempting to locate a “centre” from which all Hindu authority stems out of (which is what Hindutva groups seek). This automatically assumes the position that the ‘tribal’ people are always the ones who “take” ideas and concepts and divorces them of a knowing and conscious exchange with Hindu “missionaries”, maybe even resistance. The control room is not in Gujarat, Maharashtra or Ayodhya. If anything, we see the reverse, that in fact, Hinduism has always been shifting and ‘de-centering’ itself according to contexts and areas. The question “were/are Khasis, Hindus” is inextricably linked to the notion of who a Hindu is in the first place. The flexible and assimilative nature of Hinduism ensured its success from Cambodia and Bali through to Kabul etc, it spread through a huge geographic expanse. However, this strength, this mutability is also what permits the Far Right groups to go about proclaiming everything and everyone as being Hindu, everything from “proper” religions like Buddhism and Jainism to smaller belief systems like Niam Khasi (Meghalaya), Donyi Polo (Arunachal Pradesh) and Meiteism (Manipur). Their success in redefining the latter practice as their own is something the Niam Khasi followers should be wary of. Ultimately, religion is less important than politics.

Beyond religious debates in Khasi-Jaintia Hills

The water seems to have cleared up a bit and so maybe it is the right moment to dip one’s feet in the pond – unsettle things. There has been a large amount of correspondence in the Shillong Times – back and forth – around the issue of whether our local “indigenous faiths” (and those following them) should qualify for “minority” status. If they attain the desired outcome, possibly through reservation, then the perks and advantages attached to “minority” would be open to them (more so than before). So there have been various quarters that have taken this up as an issue for debate. There are some who have straight away rubbished such claims, and there are others who have taken to defending them. Few have said that there is no need for ‘reservation’ because there is no such discrimination against the NiamTre or Niam Tynrai followers. This is hardly correct (more on this later). Still others have got around to philosophizing and discussing the nature of religion, definitions of faith and other stuff. Of them, I ask: whether they are religions or faiths or whatever, do we simply belittle the sentiments of a people who feel slighted? Do people care about the definitions or the real material conditions that they encounter in their day-to-day life?

So the key word here is “discrimination”. This main point of contention is very fascinating for our particular context. We have always, supposedly, been at the receiving end of the stick and our entire political discourse is premised on the presumption of “defense” except for this case in question. In January, I along with a researcher friend, Bhogtoram Mawroh, travelled to Mawsynram, in the company of some pastors. As we made our way along the Lyngiong- Tyrsad road, one of them turned to the other and said “Ithuh phi mo, ki jaka bym pat long Kristan” (you can recognize, places which are non-Christian, by the way they look). My friend looked at me, smirked and shook his head. He did this because we had actually talked about something along those lines much before that moment. Much of our respective works involve travelling to and visiting villages in Khasi, Jaintia Hills. Therefore, it quickly dawned on us that development patterns (roads, electricity, sanitation) within these parts of the state seemed more inclined towards one particular demographic than others (namely Khasi Christians). We are currently pursuing means to validate this supposition. This is not in any way a mission to ‘politicize’ “inclusion/exclusion,” it is for the sake of knowledge.

There are many reasons why the ‘indigenous faith’ followers might be sidelined. The major and most obvious one is because they are fewer in number than the Christians. A political representative such as an MLA would sadly be more inclined to help realize the aspirations and ambitions of the majority. Even if she/he belonged to the minority group, ultimately the majority would have to be satisfied if she/he were interested in being re-elected for the next term. To change this would be far and away an extremely arduous but necessary task. However, even if a more “representative” representation were achieved, the systemic discrimination would be harder still to overcome. How would one begin to confront the privileges accumulated over decades that have been enjoyed by the Christians? How would one begin to unwind the ‘power’ cliques and political “spaces” that have become their prerogative? Would a form of reservation really do anything to uplift the plight of the ‘indigenous faith’ followers? Would it be constructive in the long run, or would it tear our community asunder?

The conclusion I surmise is that this is essentially a critique on the very idea of “reservation” itself. I am not against the idea, I think it is absolutely essential for a more just and egalitarian society. However, even as we ‘rejoice’ in the status of being a Scheduled Tribe (ST) we must acknowledge the bitter reality that most of the benefits and advantages of being ST are enjoyed by the middle and upper classes. I doubt that the poorer sections of our society, and especially those in the villages, can claim to have gained much from an ST/SC certificate. This is the danger too with the current plea by the Sein Raij and co. I am sure they would have thought hard upon this as well. If the minority benefits all go to a Niam Tynrai businessman’s family in Shillong and not villagers like those in Lyngiong-Tyrsad then it would have failed in its objective, in my opinion.

I think that the way forward is to reach out to one another, calling out progressive Christians and non-Christians alike to come together and attempt to alleviate the suffering of others. Orthodoxy, on all sides, is the enemy. In this regard, we have to grow bonds stronger than the religious ones. Pressure and lobbying groups that can bring people together rather than pull them apart should be encouraged. For this to happen, we need dialogue. It might be painful, embarrassing even but it must be initiated. We do not need “outsider” organizations to come and perform charity puja. In our need for political allies and powerful friends we seem to forget that we have more in common with each other (Christian and non-Christian) than Right wing nut-jobs who seek to further widen the schism. This is as true for the Hindutva as it is for the Evangelical Fundamentalists. The tragedy could be that these characters might actually come together to vilify and demonize Muslims (the “dreaded” Bangladeshis) O what a big joke that would be! That cannot be allowed to transpire without resistance.

Frankly speaking, the Niam Tre/Tynrai already have a trump card. On the cultural front, they have won and politics and culture are intertwined. Unless they approach the matter with open-mindedness and self-criticism, Christian Khasis can never truly be “Khasi” again. There are many who would raise objections to this statement and they have interesting points to make regarding definitions of identity, language, customs etc. My point, however, is that from within a conservative or orthodox Christianity (which is most of our Christianity!) we cannot ever (through fear or censure) really know what it is like to be “Khasi.” I realize that many might have problems with my investing so much authority with the Niam Tre et al. After all, are they not also modern? Have they, also, not been changed by the times? How could they survive if they were static all this while? The Niam Tre et al have undoubtedly altered as well but in terms of cultural luggage (the folktales, the beliefs, the songs, dances) they are probably our best custodians. They could be actively teaching the Christians a few things about our common past and maybe with that our collective futures would be clearer, brighter. There would be no need for “defense” or preservation then. They can be the initiators of real ‘growth’, but it must be inclusive.

Shaphang ka jingshah batbor ha ki rynsan jong ka internet

Kine ki shynrang Khasi. Wat lada ka jaitbynriew jong ngi ka ong ba ka burom ia ki kynthei, ka jingthoh jong kine ki briew ha kine ki pages ha Facebook ka kdew da kum wei pat. Lada ngi ong ba ki kynthei ki don shisha ka hok ban im kylluid, balei ba ki hap ban shah thad kumne ha kine ki rynsan ha ka internet. Ka met bad mynsiem kadei jong ki shimet, kam dei jong no jong no ruh. Ngi dei ban ai lad ia ki ba kin long bad leh kum ba ki kwah. Lada ngi ong shisha ba ngi pdiang ia ki kynthei kum kiba ia ryngkat kyrdan bad ki shynrang, te balei ngi nang ban kdew kti tang ia ki jingleh jong ki kynthei bad sngap jar jar ia kiei kiei kiba leh ki shynrang?

Wat lada ngi ong ba kine ki kynthei ki leh khlem akor ruh, ngi dei ban sngewthuh ba ngi long arsap namar ngim buh pud ei ei ia ki shynrang pat. Ngi dei ban burom ia ka hok jong ki kynthei khasi ban im ha ka mon ka jong Ki.

Kaba i jakhlia khamtam kam dei ki dur jong kine ki thei hynrei ka ktien jong kine ki nong post ba ki da pyndonkam shisha da ka ktien kaba khlem akor, ka ktien ka ba i ma, haduh ba ki da byrngem ban batbor bad pynthombor ia kine ki kynthei. Ka dei shisha mo kum kane ka jaitbynriew kaba ong ba pdiang ia ki kynthei kum ki “equals”?

Kine harum ki dei ki jingbyrthen jong kine ki ‘khlawait internet ‘ jong ka jaidbynriew ki bym sngewthuh ba ka jingbatbor bad ka jingleh beijot ia ki kynthei kam dei shaphang ka ‘jingkiew sex’ hynrei ba ka dei shaphang ka jingsngew donbor jong u nongleh beijot.

Kaba i jakhlia khamtam kam dei ki dur jong kine ki thei hynrei ka ktien jong kine ki nong post ba ki da pyndonkam shisha da ka ktien kaba khlem akor, ka ktien ka ba i ma, haduh ba ki da byrngem ban batbor bad pynthombor ia kine ki kynthei.

Shuh shuh ruh ki don sa ki post kiba pynsaphriang ia ka jingkhim jingmut bad kiba pyni katno ka dang jyndong ka jingsngewthuh jong kine ki briew haba ia dei bad ka jingshah batbor bad ka jingshah leh beijot ki kynthei. Hato ngin ia rkhie ne sheptieng ia ka jingsngewstad jong ki?

Are we Khasis racist?

There have been many reported incidents of racial discrimination against our fellow north-easterners in the mainland. It is a well known fact. That being said, many of us are also aware of the inconsistencies that prevail in our arguments against racism in India. The inconsistency arises when we fail to acknowledge the fact that racism is everywhere. That it is rampant even in the most modern societies.

We are a country with a commendable diversity in culture and ethnicity. Our northeast region itself is comprised of countless ethnic groups, where majority are tribal communities. One of these, the Khasis in our home State, are further divided into four sub-tribes.

Racism in our home state is well documented, and the evidence is quite abundant if one choses to search. The offshoots events in the recent ILP issue or the series of communal violence in the previous millennium are but just a few incidents of racial incidents in our seemingly quiet city of Shillong.

Many of us will often ask ourselves, as to how far can our fetish for discrimination go.

I believe most of us are racist in some way or the other. Our primal tendencies to create divisions or noting differences among ourselves is unfortunately inherited from age old legacy of our ancestors. Though the levels of racial indoctrination may differ from person to person, the concept of racism itself is being taught to the young unknowingly, and at most times without reason. It just happened. One of the outcomes of such an indoctrination is evident in the rampant offensive stereotypes that the Khasis have for each and every ethnic group they had ever intermingled with; Dkhars, Khyllahs, Riewkhlaw, Muid, etc. to name but a few. In fact, we even express a form of xenophobia towards our own fellow Khasis just because they belong to a different sub tribe.

‘Ngi, ngin da kiew dieng ngi kiew tang ha ki tnat, kan da kiew ka War, ka kiew haduh ka sla’ / When we climb trees we climb up to the branches but the War climb up to the leaves