Parents moralising to their children, demagogues exhorting the community to rise up, students sleepless at their mysteries, lovers whispering their communion, U Soso Tham‘s modern poetic reimagination of the Land of the Seven Huts haunts the cultural world of contemporary Khasi Jaintia Hills. Published in the waning years of British colonialism in 1935, Ki Sngi Barim U Hynñiew Trep / The Old Days of the Khasis was his Magnum Opus as they say. An epic length lamentation of loss of “Khasi culture”, Ki Sngi Barim U Hynñiew Trep tried to figure out a future for the Khasi community caught between a colonial modernity and a revivalist imagination. When we heard that Dr. Janet Hujon had translated and annotated this classic of Khasi literature, we had to have it on RAIOT. We thank Janet for her permission for the local outing of her translations. To support her work, you can buy the hardcopy of the book from here.

Dr. Janet Hujon, was born in Shillong and did her Masters from North Eastern Hill University, Shillong. Her PhD is from University of London. She lives in the UK.

And yes, the copyright of the translation belongs to Janet Hujon, so ask before you steal.

![]()

Janet Hujon’s introduces her translation

Then will the rivers of our homeland tear the hills apart

The year is 1935. The event, at least for literature in Khasi, is momentous. A man diminutive in stature but with a voice that cradled the vast soul of his people had decided to do what he knew best. He completed a classic in Khasi literature and the Shillong Printing Works published The Old Days of the Khasis (Ki Sngi Barim U Hynñiew Trep). Soso Tham came in from the wilderness to carve in words the identity of his people—he made us see, he made us hear, he made us feel and he made us fear.

In a land still under British rule this legendary schoolteacher expressed a weary frustration with the English texts he had taught his students year after year. He declared that from now on “he would do it himself”. And so he did. An oral culture for whom, in 1841, Thomas Jones of the Welsh Calvinist Methodist Mission had devised a script, now had a scribe whose work expresses a profound love for his homeland and an unwavering pride in the history of his tribe—a history kept alive in rituals and social customs and in fables and legends handed down by generations of storytellers.

Soso Tham refused to believe that a people with no evidence of a written history was without foundation or worth. He set out to compile in verse shared memories of the ancient past—ki sngi barim—presenting his people with their own mythology depicting a social and moral universe still relevant to the present day. For him the past is not a dark place but a source of Light, of Enlightenment. It may lie buried but it is not dead, and when discovered will provide the reason for its continued survival. Ki Sngi Barim U Hynñiew Trep is the lyrical result of dedicated devotion. It is an account of how Seven Clans—U Hynñiew Trep—came down to live on this earth. Tham tells us how

Groups into a Nation grew

Words ripening to a mother tongue

Manifold adherents, one bonding Belief

Ceremonial dances, offerings of joy, united by a common weave,

Laws and customs slowly wrought

Bound this Homeland into one

Not content to be the passive, unquestioning recipient of literary output and thought imposed by a foreign ruling power, Soso Tham decided to write in his native Khasi and about his own culture. Although he had embraced Christianity and imbibed Hellenic influences through his reading of English poetry, writing in Khasi expressed his resistance to the dominance of English—for surely, did not the Muse also dwell in his homeland? Creativity, he declared, is not the prerogative of any one culture. With the Himalayan foothills as a backdrop, winding rivers silvering the landscape, and hollows of clear pools and hillside springs, Tham points out that Khasis too have their own Bethel and Mount Parnassus and their own sources of inspiration from which to drink like Panora and Hippocrene in ancient Greece. His dalliance in the literature of distant lands had led him home.

But in throwing off his colonial yoke to mark out an independent path, Tham did so with no trace of chauvinism. His affinity with the Romantics cannot be ignored. While he worked on his articulation of a Khasi vision, Tham remained alive to the gentle unifying truths of human experience and this can be seen in his translations of William Wordsworth’s poems into Khasi.

For reasons of accessibility the nightingale (The Solitary Reaper) becomes the local “kaitor”, the violet (“Lucy”: She dwelt among the Untrodden Ways) becomes the “jami-iang”, and isn’t it just serendipitous that Wordsworth’s Cuckoo should so fit Soso Tham’s like a glove? This is because her call is heard in the Khasi Hills as it is in the Lake District. So when Tham addresses the bird as “queen of this land of peace” I feel he has not mistranslated the line “Or but a wandering voice?” but has chosen instead to give this spirit of the woods “a local habitation and a name”. The Khasification of the cuckoo is complete and a mutual recognition of the need to cherish what we have is established. Perhaps Wordsworth did us a favour, for without his poem Khasis may have never benefited from Tham’s translation thus opening our ears and hearts to this denizen haunting our woods.

Poignant sadness in the face of beauty lost or just out of reach, so moving in Keats’ Ode to a Nightingale, is also felt in Ki Sngi Barim: inevitable perhaps in a piece recalling the past amidst a perilous present. Keats is therefore a gentle presence in Tham’s work, for listen:

High on the pine the Kairiang sings

About the old the long lost past,

Sweetness lies just out of reach

And such the songs I too will sing

Stars of truth once shone upon

The darkness of our midnight world

Oh Da-ia-mon, Oh Pen of Gold

Put down all that there is to know

Awaken and illuminate

Before the dying of the light

Furthermore, scenes from a Hellenic past in Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn dovetail neatly with the Khasi homeland where forces of nature each had their own deity. Ki Sngi Barim testifies to the ancient Khasi belief that the green hills, forests, valleys and tumbling waterfalls are guarded or haunted by their own patron deities and spirits. Reverence or fear has traditionally served to protect the natural world. Soso Tham himself might well have asked:

What leaf-fringed legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities of mortals or of both

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

With their own world of sacred ritual and sacrifice Khasis would also have understood:

Who are these coming to the sacrifice?

To what green altar, O mysterious priest

Lead’st thou that heifer lowing at the skies

And all her silken flanks with garlands drest?

Discovering the resonances between the English literary canon and Khasi poetry has undoubtedly been a source of pleasure because for me they underline the human stories we all tell. But this was not necessarily Soso Tham’s intention. What he wanted to do was to correct a gross misconception that still scars and skews the way Khasis look at themselves vis-à-vis western culture. His aim was to rebuild and restore cultural pride. Recounting the carefully laid down rules of social conduct, the heated durbars where systems of governance were debated and established, and the fierce fighting spirit of fabled warriors, Tham challenges the derogatory labelling of his people as mere “collectors of heads” or “uncouth jungle dwellers” incapable of sensitive thought and action.

Once Great Minds did wrestle with thought

To strengthen the will, to toughen the nerve

Once too in parables they spoke they taught

In public durbar or round the family hearth

In search of a king, a being in whom

The hopes of all souls could blossom and fruit

and

Boundaries defined, rights respected

Trespass a taboo remaining unbroken

Equal all trade, fairness maintained

Comings and goings in sympathy in step

Welfare and woe of common concern

Concord’s dominion on the face of the earth

What the poet constantly underlines is that a homeland and a way of life that has survived for centuries cannot be dismissed as insignificant—his ancestors were accurate readers of the writing on the land heeding the lessons and warnings inscribed on “wood and stone”. It is this wisdom that accounts for the continued existence of a unique people who, until relatively recently, lived life in tune with their natural surroundings and in sympathy with one another. This is why when Soso Tham renders in words the inspiring beauty of his homeland he does so with profound love and reverence, declaring with absolute conviction:

Look East, look West, look South, look North

A land beloved of the gods

With a pride so touching in its childlike certainty he expects no dissent when he asks:

Will the high Himalaya

Ever turn away from her

Pleasure garden, fruit and flower

Where young braves wander, maidens roam

Between the Rilang and Kupli

This is the land they call their home

To fully appreciate why Soso Tham is the voice of his people, one needs to know how Khasis respond to the world around them, and we must profoundly reflect upon this if we are to piece together again the shattered vessel of our cultural confidence. Here I recall what was for me a blinding flash in my understanding of the workings of my mother tongue. Years ago while we were travelling on the London Underground, my cousin made the following observation about an elevator carrying the city’s crowds. In Khasi she said: “Ni, sngap ba ka ud”. This would be the equivalent of saying: “Oh dear! Listen to her moan”. Simply because the old grimy elevator had been assigned the status of a human being and specifically that of a woman—“ka”—I immediately empathised with “her” suffering. In English the elevator would normally have been referred to as “it”, and I am convinced that my imaginative reaction to it would have been bland if not altogether non-existent.

On that day I rediscovered the creative roots of my mother tongue. I was reminded that not only do Khasis see living beings, natural forces and inanimate objects as either male or female, but they also endow them with human qualities and feelings. It is this innate poetic tendency that makes the world come alive for every Khasi and no one exemplifies this better than Soso Tham. So when he writes about the great storms that batter Sohra, we are left in no doubt that here we are dealing with a living breathing entity, human in essence but with far greater power to awe:

So the waterfalls threaten and the rivers they growl

They sink to the plains and they smother the reed

They banish wild boar who have ruled unopposed

For that is the way our mighty rains roll

Rivers turn to the left and advance on the right

They collide with and devour whatever’s in sight

Small islands appear as rice fields are sunk

The might of the Surma gives the Brahma a fright

Tham’s words beat in time to the tempo of the natural world with which he so closely identifies, so that the storm lives through the poet and the poet lives through the storm. The poet is the storm. The vivid description provides an insight into what informs the hill person’s view of the natural world—this being the ability to respond with both awe and enthusiasm to the might and capriciousness of Nature. For a Khasi to underestimate the significance of perceiving, evaluating and identifying the effects of the natural world on them would be dangerous if not fatal. Yes we can delight in the Khasi flair for storytelling seen in Tham’s descriptions of gentle charm, sweeping majesty and lively engagement, but it is more important to heed the passages inspiring fearful dread. In a land burgeoning with promise and flowing with contentment the sonorous toll of doom is never ever totally muted. Then and even more so now that sense of foreboding cannot be ignored.

In the process of translating I came across the word “tluh” which Tham used in connection with his first poetic breakthrough when he was translating the English poem Drive the Nail Aright Boys into Khasi. I had to look up the word because it does not form part of my everyday use of Khasi. When I found out that “tluh” is “a tree—the fibres of which are used to make ropes, or improvise head-straps, strings”—I felt both enlightened and apprehensive. I felt enlightened because I realised that a whole world of Khasi knowledge and expertise lay in just that one word. But elation was soon replaced by dread.

In his book Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees Roger Deakin mourns the fact that “woods have been suppressed by motorways and the modern world, and have come to look like the subconscious of the landscape […] The enemies of woods”, he says, “are always the enemies of culture and humanity”… and this is what made me apprehensive. Had I not come across the word “tluh”, I would never have discovered the world to which it refers. How much more do I not know? How much more have we lost? I therefore marvel not only at our poet’s appropriate choice of image but I also value the lesson he points us towards.

Today the Khasi and Jaiñtia Hills form part of Meghalaya, a state in North-East India which came into being following local demand for the recognition of a strongly felt tribal identity. But it is clearly evident that long before this overt political step was taken Soso Tham had already addressed the question of identity, carrying with it that sense of rootlessness deeply embedded in the Khasi psyche, a raw wound sensitive to the reminder that “the Other” whom we have encountered in our recorded history has invariably been certain of his or her historical beginnings. This, I feel, accounts for the leitmotif of sadness running through Khasi literary and musical compositions, and the numerous nuanced terms for sadness and regret. Tham speaks for so many when he asks:

Tell me children of the breaking dawn

Mother-kite, mother-crow,

You who circle round the world

Where the soil from which we sprang?

For if I could, like you I’d drift

Down the ends of twelve-year roads!

Ki Sngi Barim is both a love letter to his homeland and a troubled and troubling exploration of what makes and sustains that fragile sense of self. He sees the battle for identity being waged on two fronts—against the enemy without and the enemy within. A reading of the work reveals in no uncertain terms that Tham fears the enemy within more than he does the foe without. Tragically this is still the case today. Mineral-rich Meghalaya with its dense forest cover is now a treasure trove being exploited by the rapacious few using tribal “rights” over the land as justification for their actions:

Man’s greed is now a gluttonous sow

(A pouch engorged about to rip)

Ki Sngi Barim is trenchant social critique told through a trajectory of spiritual questing. Through the converging prisms of Khasi myth and religion, Tham tells the universal story of temptation and man’s fall from grace. But despite the poet’s despair hope is never totally lost, for the narrative journeys towards the possibility of rejuvenation as we see in the final section Ka Aïom Ksiar (Season of Gold):

The Peacock will dance when the Sun returns

And she will bathe in the Rupatylli

O Rivers Rilang, Umiam and Kupli

Sweet songs in you will move inspire

Land of Nine Roads, pathways of promise

Where the Mole will strum, the Owl will dance

Spellbound by the beauty of his homeland, the poet steadfastly holds on to his belief that the land that he fiercely cherishes and that inspires his art will once again be a spring of renewal and creativity. Whatever else this translation may achieve, my hope is that the powerful life of an old tradition will reawaken so that when we read we will hear:

The crash of rivers, the thunder of waterfalls

In the Khasi minstrel’s reed-piped-ears

Where tumult is hushed and silence then ripples

To the furthest brink of infinite time

Perhaps the human voice will once again reassert its power to empower and change:

Then once again will forests roar

And stones long still shake to the core

![]()

A short guide to Khasi origin tales

Long, long ago before anyone can remember, there was a Time we now call the Ancient Past. She holds and protects all the days that once were young but have now grown old, that once were new, but now have aged. No one has ever seen her, but we all know her. Khasis call her Myndai or Ki Sngi Barim—the days that make up Time long gone.

In that Time lived peace and harmony guarded by the Seven Families, who, in answer to the prayers of the Great Spirit of Earth, Ka Ramew, were sent down by God to care for all living creatures and forces—rivers, trees, animals, flowers, fruit. From their grass-thatched homes (Ki Trep) the Seven (Hynñiew) went forth, increased and multiplied. These Seven Families are the first clans, the mothers and fathers of all Khasis today. They are the Hynñiew Trep.

Although they lived on earth, the Hynñiew Trep were able to visit the other Nine Clans who still lived in Heaven. They could do this because there was a Golden Ladder bridging the space between heaven and earth. This ladder was on the sacred mountain—U Lum Sohpet Bneng—a mountain that stood at the centre of the world and was therefore known as the navel of heaven—u sohpet. The Golden Ladder was the umbilical cord linking terrestrial beings to their celestial beginnings.

So for a time all on earth was as God had ordained until the Seven Clans forgot their duty to their Creator and to one another—to Tip Blei, Tip Briew—to know and honour God and each other. Swallowed by Greed they were reborn as creatures who no longer saw with the eyes of contentment. They no longer revered the might of the great mountains and waterways that protected and fed the green world they lived in. They feverishly took from the earth, refusing to listen to her cries of protest. Finally, exhausted, the earth fell silent.

God looked down in despair at his chosen people. Custodians appointed to care for creation had broken their word. Anger grew in his heart. He turned his face away and destroyed the Golden Ladder. From that day onwards the Hynñiew Trep never again knew the freedom of being allowed to walk in heaven.

Their misfortune increased when a monstrous tree—the Diengïei—began to push its way through the soil. The tree grew and grew until its branches covered the face of the earth: a canopy so dense that not even the strength of the sun’s rays could push through. The land lay dying yet the Diengïei kept growing. Stricken with terror the people seized their blades and axes and began to hack at the solid trunk. They knew that without light they too would die. Every evening they returned to their homes having left a gaping wound in the trunk and always determined to return the next day to finish their task. But each morning they returned to find the wound had healed. The trunk looked as good as new. What was going on?

Worn out and weary in spirit the people looked at each other in despair. Then suddenly in the silence they heard the voice of the Phreit, a tiny wren-like creature—“If you promise to spare me some grain after every harvest, I will tell you why all your efforts are in vain.” At first the people refused to believe her, but seeing no other explanation for this mystery, they agreed to grant the little bird’s request. “From this day onwards” they said, “You and all your descendants will always have a share of our harvest.”

And this is what the Phreit told them: “Every night after you return to your homes, the Tiger arrives and licks the cut clean. By morning the tree is renewed and the gash is sealed. So no matter how hard you hack you will not be able to fell the Diengïei.” The words of the little bird plunged the people into an even deeper darkness. Then she spoke again: “But I know a way out of this.” Immediately they looked up. “Tell us,” they implored, “Tell us little bird!” “This is what you must do. This evening, before you go home, leave an axe in the wound of the tree. Make sure the blade is facing outwards”. The people did as they were told. In the morning they returned to find a blood-stained blade and the tree unhealed. It was not long before the mighty Diengïei came crashing down. Light and life returned to earth and the people remembered to keep their promise to the Phreit.

But one day darkness once again returned to the earth and this is how it happened:

For a while the people remembered their suffering. They kept the laws and looked out for each other. With the return of peace and harmony they decided to celebrate life in a dance to which the Sun, her brother the Moon, and all living creatures on earth were invited. Arriving late after her day’s work, the Sun abandoned herself to the happiness of the moment as she danced with her brother in an arena by now emptied of all other dancers.

Suddenly a hum like the moaning of bees and wasps rose into the air: murmurs of disapproval from the crowd that watched the siblings move in absolute surrender to the joyous freedom of the dance. Doubts darkened the onlookers’ minds—should a brother and sister move together in such blatant unison? Had they broken the most sacred of all taboos? The clamour grew louder and finally became so unbearable that the Sun decided to leave, but not before she had vented her rage on the crowd for their harsh and hurtful words. “Never again”, she said, “will I bring you my blessings of warmth and light.” With those ominous words hanging in the air she left and plunged into a deep dark cave—Ka Krem Lamet Ka Krem Latang. Because the people saw evil where there was only joy and shame where it did not exist, they were punished. And once again human beings had to look for a way out of Darkness and into Light.

Time became an unending stretch of all-enveloping night in which the people were lost. Filled with remorse they pleaded with the Sun but she refused to emerge. Who could they find to placate the enraged Sun? Then Hope came in the form of the lowly Rooster—an unadorned creature who hid in shame from other living beings. If the people draped him in beautiful silks, he said, he would feel confident enough to stand before the nurturer of life and bow before her flaming throne to plead their cause. The people agreed. He was garbed in the finest and richest of silks—the fabric reserved for the rich and for royalty. When they had finished he had been transformed. Turquoise melted into the dark blue of night. Carmine, terracotta and gold fired the gloss of darkness while grey and white flowed in gentle stripes. And as the ultimate mark of distinction a red crest was placed on his head. Before them stood a prince!

He set off on his long journey. Often he took shelter and rested in the branches of the rubber tree and the venerable oak. Finally he arrived at the entrance of the Krem Lamet and in his many-splendoured robes he faced the Sun. With a voice clear and true he said: “I stand here before you O Great Being to seek your forgiveness for a people who now know they acted in ignorance and have repented. I have come here to offer my life in exchange for their freedom from this punishment. Return to their midst, Great One, restore light to their lives.” Moved by his simple request and selflessness, the Sun not only relented but also spared the Rooster’s life.

The Rooster bowed in humble thanksgiving and said: “From now on, O Great Being, I will remind myself and the world of the mercy you have shown us. At the beginning of each day I will announce your coming with a bugle of three calls so that all living creatures will know you have returned in order that the earth might live.”

As a token of remembrance for the kindness shown to the Rooster by the rubber tree, the oak, and the leaf (Lamet), these three are always included in Khasi rituals, commemorating forever the significance of Gratitude and Memory in the lives of the Khasis.

KI SNGI BARIM U HYNÑIEW TREP

1. Ki Symboh Ksiar / Grains of Gold

The opening lines of Ki Sngi Barim U Hynñiew Trep explain why Soso Tham decided to compose his magnum opus. Saddened by the fact that his people continued to look elsewhere for inspiration while failing to appreciate the cultural wealth into which they are born, he set out to reclaim and record the past—ki sngi barim—that survives in myth. He tells of a time now lost to us when the Khasi and Pnar people, who call themselves U Hynñiew Trep, came to be here on earth. This is the “Once upon a time” section of that story referring to legends and tales told and shared, of a common heritage of the imagination that has held a people together.

![]()

Know not the light within our land

How long ago far back in time

Our ancients did new worlds create

For then the Seven lived apart

Impenetrable heavy was the dark

Among the Stars the Sun and Moon

On hills and forests, spirits roamed,

Man and Beast, the Tiger, Thlen[1]

United by a common tongue

Before the grim macabre took hold

They worshipped then the One True God

The Spoken Word was then revered

The humble Phreit[2] was honoured, fed,

Hard they toiled from dawn to dusk

Knowledge cached within the womb[3]

From where our legends sprang to life

And wingéd sprites sung into being

Of signs and symbols some did speak,

“From here,” some said, “Came forth the Thlen;”

“Sin and Taboo? Whence that flood?”

“From here”, they cried, “From Lum Diengïei:”[4]

But of the One, no one had doubts

Why He was called “U Sohpet Bneng”[5]

Of God and Sin, so too of Truth

In parables as one they spoke

Old voices tell of visions draped

By Ka Rngai[6] for all mankind

Some stars live on in scattered gardens

The rest have drowned in forests deep

To banish Sin, to bear the yoke

In the Sacred Cave[7] far back in time

The fearless Cockerel rose upright

“I wait the word from God above.”

A Creed was born—its rites revered

By children of the Hynñiew Trep

Tears from a mother’s pain-wracked heart

Shadow the bier which bears her son,

Fingers strum, recall the tale

The legend of the noble Stag

The rusted Arrow piercing deep

The rushing flood of bitter tears[8]

Signs once clear on boulder rock

Remain unread, obscured, weed-choked,

Where Orators Thinkers once declaimed

Spoke in tongue unknown to us,

Yet hilltop stark and sheltered shade

Wood and Stone still speak to man

Ancient race—Khasi and Pnar

Ranged across the earth’s arm span

Hidden light waits to be found

In modest thatch and humble roost

To help us peel, push back the dark

Restore the light from days of old

Around the world we search for Light

Yet scorn the light that shines at home

The glorious past will dawn again

When seams of lustre-lost we mine

The seed of light his vibrant root

Into the Past he pierces deep

Gleam of sky on rock we’ll see

When sun-showers stop and fade away

Dark dense clouds retreat in fear

As the rainbow rises in the sky;

Libations pour, O Golden Pen

Emblazon with colour the blinding dark!

—–

[1] The Giant Snake which promised wealth to his worshippers, and had to be kept happy by human sacrifices.

[2] Munia, Spotted Munia, Red Munia etc. A little wren-like bird, which helped mankind.

[3] Khasis believe they lost their script in a great flood. The Khasi thought his precious script would be safe in his mouth but he swallowed it as he battled the raging waters.

[4] The hill on which stood the monstrous tree (Ka Diengïei) that covered the earth—a sign of God’s displeasure

[5] “The Navel of Heaven”

[6] “Ka” denotes the feminine (as “U” denotes the masculine). “Rngai” is a word with shadowy connotations pointing to spectres, phantoms, the unreal yet powerfully real in the potency of its effect. So here “Ka Rngai” is a powerful female force.

[7] The sacred cave into which the sun retreated, angered by the aspersions cast on her by those who attended the Dance of Thanksgiving

[8] This is a reference to what is known as “The Khasi Lament”—a song of grief pouring out from a mother’s heart when she discovers the body of her wayward son who, against her wishes, had strayed too far from home. He dies from the wound inflicted by an arrow. Archery is still a common pastime in the Khasi and Jaiñtia Hills where the Khasi and Pnar (Jaiñtia) people live.

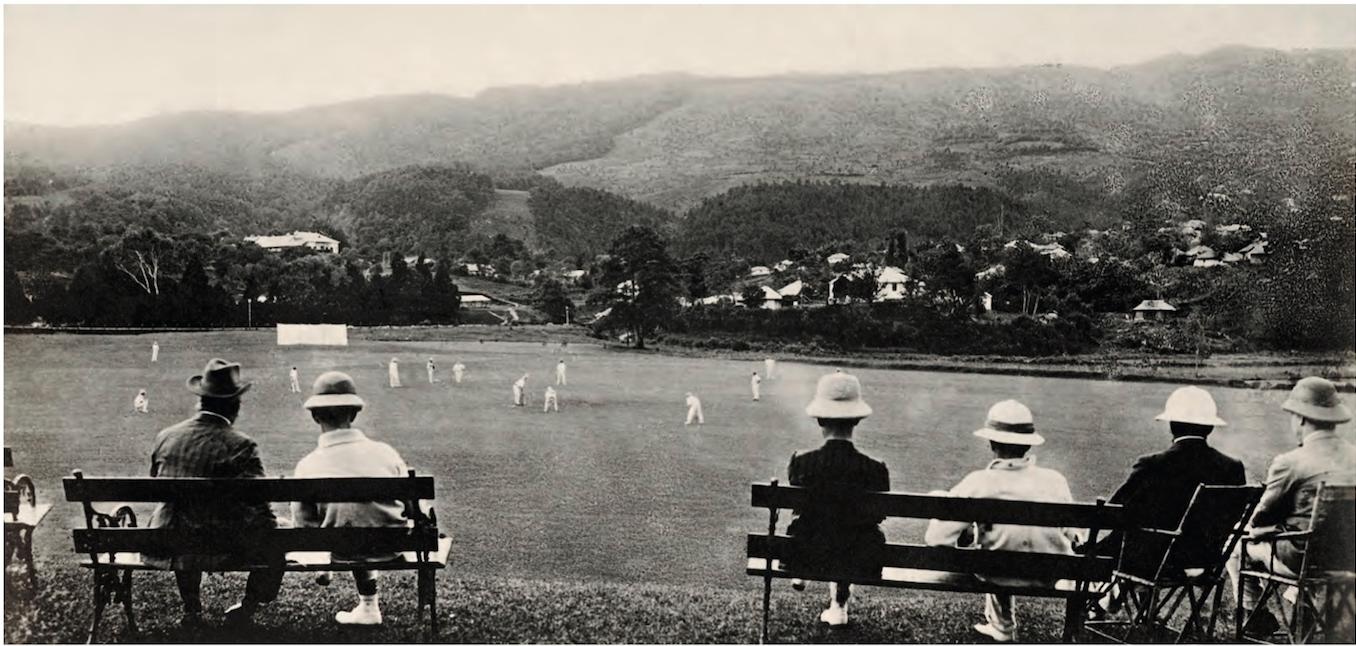

2. Ka Persyntiew / The Flower Garden

Evocative of Eden, this section describes the haunting beauty of Tham’s homeland. Although the Khasi and Jaiñtia Hills have been plundered for their forest and mineral wealth there still remain large tracts that are heartbreakingly beautiful, able to stir wonder today as they did in the distant past. That poignant longing for what once was is as acute now as it was when Soso Tham composed his masterpiece.

![]()

On bracing hillcrests, shielded lee

Refreshed I walk, alone reflect

Upon my homeland’s darkened heart,

Then under every thatch I find

Scattered grains of thought profound

Alive in pools of haunting tears

Golden grains forgotten old

Abandoned random still remain

As when in fresh fields left behind

Rice potato millet yam

Each with a bygone tale to tell

Of what was sown, of what has been

The bird still calls within the wood

The kite she casts her eye afar

Melodies I weave to make a song.

Swift I turn in an eye’s quick blink

To shake awake from biers extinct

The Ancient Past of the Hynñiew Trep

Once this land was still untouched

Unpeopled empty pristine void

Then the Seven first came down

To loosen the soil, to plough the land,

Filling gardens with flowers, orchards with fruit

A land where the human race could thrive

To far-flung corners soon they spread

Their yield increased their harvests rich

Fruit plantations, betel groves[1]

Grains of gold strung to adorn.

The wilderness rumbled, boulders crashed

Tumult echoed, shook the land

Groups into a Nation grew

Words ripening to a mother tongue

Manifold adherents, one bonding Belief

Ceremonial dances, offerings of joy, united by a common weave,

Laws and customs slowly wrought

Bound this Homeland into one

The world was then a different place

Birds soared freely, beasts at peace

Out in the open or concealed from sight

Flowers with ease communed with man,

Submerged beneath the tangle-weed

Thirty-thoughts-have-sprung-from-two… where quiet blooms U Tiew Dohmaw[2]

Peacocks danced with wild abandon

Wild boar rolled in cooling mud

In deep dark pools Sher[3] supple dart

Under sheltering fern the doe lies quiet

The courting call of U Rynniaw[4]

Lulled nodding monkey, capped langur

Grazing stags on tender green

Sleeping tigers in the gloom

Cooling hills warm days just right

While wild nymphs splash in waterfalls.

Look East, look West, look South, look North

A land beloved of the gods

High on the pine the Kairiang[5] sings

About the old the long lost past,

Sweetness lies just out of reach

And such the songs I too will sing.

Then once again will forests roar

And stones long still shake to the core

Will the high Himalaya

Ever turn away from her

Pleasure garden, fruit and flower

Where young braves wander, maidens roam

Between the Rilang and Kupli[6]

This is the land they call their home.

—–

[1] The betel nut is central to Khasi social and religious culture. The serving and chewing of betel/areca nuts (kwai) along with a betel leaf of the Piperaceae family (tympew) and a dab of slaked lime (shun) is never absent from a Khasi home, so much so that a folk tale grew around a tragic friendship involving the three. See Bijoya Sawian, ‘How Paan Came Into Existence’, in her Khasi Myths, Legends and Folk Tales (Shillong: Ri Khasi Press, 2006), pp. 12–14.

[2] Anoectochilus brevilabris belongs to the group of Jewel Orchids. Tiew Dohmaw literally means the flower which kisses the stone. This tiny flower, with its velvety leaves, blooms against boulders and rocks in the Khasi Hills, usually halfway up a gorge—hence it is not often easily visible. The sight of such vulnerable beauty, of fragile softness against enduring hardness, inspires the poet to contemplate this natural phenomenon. Hence “Thirty-thoughts-have-sprung-from-two”. Man and plant commune in silence.

[3] Lepidocephalichthys guntea. A small fish found in streams and in paddy fields. The full name in Khasi is “shersyngkai”—I have used the shortened version. Syngkai means waist, so the name evokes the supple twisting movements made by these fish as they twist and dart in the water.

[4] Greater Racket-Tailed Drongo. In a folktale he is cast as King of the Kingdom of Shade and falls in love with Ka Sohlygngem (Ashy Wood Pigeon) whose parents warn her against marrying a rich man. Unwilling to cause her parents any more grief, the selfless leaves and flies away. Even today the cries of the haunt the forest shade as she searches for her lost love.

[5] Chestnut-backed laughing thrush now endangered, but once common in Sohra, where Soso Tham was born

[6] The names of rivers in the Khasi and Jaiñtia Hills respectively

3. Pyrthei Mariang / The Natural World

The natural descriptions here are just as beautiful as in the preceding section but the poignancy is sharpened because they are set down in a mood of sad recollection. This is why the poet begins this section with a plea for inspiration as he seeks to fulfill his task of restoring the wonder and virtues of the past. This long look into the past from a present that is found to be wanting, creates a seam of tender pain which runs right though the composition springing from the tension that exists between what was, what is and what still might be. This in fact is a feature of a composition illustrating how the past, the present and the future coexist in a relationship of troubling unease. The poet goes in search of U Sohpet Beneng who represents the now severed umbilical cord that once linked Heaven and Earth and is “the He whom I love” now lost to humankind. U Sohpet Beneng is thus shown to be the mediator between God and Man.

![]()

Stars of truth once shone upon

The darkness of our midnight world

Oh Da-ia–mon, Oh Pen of Gold[1]

Put down all that there is to know

Awaken and illuminate

Before the dying of the light

O lift the gloom and lead me on

Away from shadows cast by trees,

Along the paths of silver streams

Draughts of wind-fresh I will drink

On cascade summit, abyss verge,

Oh where is He, He whom I love![2]

Gradual was the dawn of light

In that age of innocence

Truth seeped slowly through our ears

Those echo-chambers built of stone

Scenic splendour in the sky

We took our time to see the sun

Roused by gentle springtime winds

The sun begins her journey down

Footprints green she leaves behind

In open fields and hidden shade

Life was pure, we were held safe

As children in our parents’ laps

Just before the Autumn calls

Insects, birds break into song

Steeped in joy the land, the living

And tranquil rests the mind of man

Then surged that flow of gold-glint tears

Its headspring though… he could not find

Perhaps the Spirit Queen of Earth

Sees with vision bright and true

How stars from teardrops congregate

In waters of an endless ocean.

Into the Garden, God steps down

Beguiling time away with man[3]

On distant peaks they linger

Those children of the gods

Their eyes rest soft on earth’s great rivers

As they listen to the Riyar’s song[4]

Peace contentment reigned supreme

Before the Heavenly Cord was cleaved[5]

Our streams and rivers flowed along

Well-traced paths on boulder rock

So too the Golden Ladder scaled

Movement safe from dawn to dusk

Night a time of sound repose

Day was mother to a virtuous race

Under a roof soot-sodden thick

Night plucks the strings—kynting-ting-ting

A blush burns deep on a girlish cheek

Intense the gaze of the perfect moon[6]

Dried fish and rice my mother served

What joy replete in humble fare

Slander shunned, deceit abhorred

Truth in its prime stood resolute

The skies a clear cerulean blue,

Gently passed that time of gold

When those who trod the skin of earth

Were all held fast in God’s embrace

Then the land was free of taint

In sun-brief moments ripening swift,

And there amidst the blossom, fruit

The faces of young maidens, men;

If there be other wondrous lands

To them O then do let me fly!

—–

[1] Khasi pronunciation of the word “diamond” which I have retained to sustain the rhythm.

[2] From the point of view of those who retain the indigenous faith, this is a reference to a Saviour who will restore the Golden Ladder between Heaven and Earth. From the point of the Christian Khasi this is a reference to Christ. Soso Tham was a devout Christian.

[3] An approximate translation of the Khasi expression “ïaid kai”. The adverb “kai” suggests a mood that has no single English word as an equivalent and yet is very much a part of Khasi identity, and it concerns me that in a world fixated on status and material success, we might be losing this trait. We have banished ourselves from Eden to enter the rat race whatever the cost. “Kai” possesses a sense of pleasurable purposelessness. “Ïaid kai” (rambling, strolling in the manner of a flaneur); “shongkai” (sit around), “peitkai” (just looking), “leitkai” (a leisurely outing) and so on. Perhaps “hanging out” or “chill” best approaches the feeling contained in the word although both these words indicate an attitude that involves premeditation or conscious choice and therefore do not possess the relaxed spontaneity of the easy going “kai” which has a connotation of freedom to roam, to look, to relax—“for free”—in a world that is not bound by the demands of time. Even the act of voicing the gliding diphthong “ai” is a long drawn out process expanding time and gently seductive. So the fact that God came down to “ïaid kai” in this plausible Eden in the Khasi hills underlines a sympathy for natural harmony that permeates our being and I hope will not be totally erased from our troubled state gripped by the tightening coils of corruption vividly described in Ki Sngi Barim for yes, as in the Biblical Eden, Tham’s Ka Persyntiew (The Flower Garden) also shelters a dangerous embodiment of evil—the serpent.

[4] A songbird in the Sohra region.

[5] when the Golden Ladder between heaven and earth was cut.

[6] No matter that the Moon is male in Khasi, the beauty of this heavenly body is celebrated as in other cultures. A handsome young man is compared to a perfect moon who has bloomed for fourteen midnights.

4. U Lyoh / The Cloud

This is the point to which the preceding sections have been journeying. Here we come upon an utterly bleak apocalyptic scene which Soso Tham fears will replace the green fecundity and harmony of his homeland if Khasis betray the Laws and Truths with which they came into this world. Soso Tham’s dramatic description of opportunist worshippers of Mammon is as accurate today as it was then. Imagery from the natural world and Khasi myth powerfully portray the dysfunctional hell to which we are going to descend as a people who are powerless to resist the temptation of worldly wealth. The poet had good reason to be fearful. Evident today are plundered forests, rivers poisoned by the unscientific extraction of coal, exhaustive sand and limestone mining, and hills bulldozed out of shape to create highways to “development” and wealth for a few—the list continues to grow.

![]()

Free of want once lived our children

Before the ox betrayed his Maker[1]

Fruit ripened red, stalks fleshed with grain,

Each day brim-filled, each palm grain-full

Daylight hours of peaceful toil

Before the virtuous took flight

Courteous speech well-learnt, well-honed

Advice on restless sleep unknown

Laughter rippled, gentle ease

Beneath the solace-shade of trees,

But far away the Eagle King

Saw signs of disquiet, portents of unease

Before the Diengïei’s cover spread

Moves with stealth the reprobate

Slowly climbs the threatening cloud

Thickening smoke from pyres untended

Obscured the sun from mountain peaks

A tribe abandoned by their God

A swarm of bees without a queen

Wandering, lost, directionless

Criss-crossing blind through open skies, stumbling into thickets deep

Nine remain in the House of God

Dispersed on earth were the Hynñiew Trep

From heaven estranged—U Sohpet Bneng slashed

As he swims through earth’s dark waters

Man sinks down to unplumbed depths

To black-hole dread in no-end caves

To deserts parched and wetlands rich

As far as Nine Infernal Tiers

Where all alone he seeks to feel… the spasms of a wished-for birth[2]

The serpent’s lair within a cave

Its blackness heavy with his stench,

Below—the coils of languorous power

Above stands She!—The Mother of the Thlen.

Just such a nest is the human heart

A place where Evil lays her eggs

God looks down and shakes his head

Sees toads and frogs eat Suns and Moons[3]

Humped dwarves, Scorpions, Snakes

Infinite hordes defying count

The Age of Purity has lost her throne

Triumphant the Pasha of the Enslaved

His eyes shut-blind seamed tight with pus, his ears no longer can they hear

His children dulled by blunted thought

For Darkness is Queen, and Ignorance rules

Fear and Unease their subjects now,

So wonder not if we should find

Devils mingling with mankind

All that remains is barren rock, fertility long since washed away

Settlers, settlements ruined destroyed

The pleasure garden once so loved

Forsaken now, she’s left bereft,

Days of peace must surely end

When the dark cloud drops and shrouds the light

Slow inch by inch the toad consumes

The sun gripped tight in her clamping jaws

While poverty, hunger, suffering, woe

Hereditary taint suck clean away… the marrow from the land.

In under-floor gloom a seed once thrived

Why now is it pale yellow in the dark?

Infernal beings deprived of sight

Collide and stumble, trample all

The race, the clan begins to shrink

The face made foul by ugliness

With honour dying in the heart

The face has lost its source of light

And will so appear forever more

For the indwelling Soul has taken flight.[4]

The blacksmith’s wares in full display

But was hammer-strike on anvil heard?

In murky gloom among the rafters, the intruder waits for night to fall

Is there a being more sinister than he hell-bent on chicanery?

Broodings foul of ill intent

Increase in strength, convene within

For verily now they are “the gods”,

Where hides the Queen[5] of the floundering bee

As sightless now he gropes his way

In a frenzied search for the Goddess Wealth

She who flies through cave and crevice

Rustling through unsightly weeds.

To cities, plains and borderlands[6]

Where man has journeyed to earn a living

Seeking out sustaining grain

Rice the lure, the face assumed by the Goddess Wealth[7]

No longer then can we discern

Waving palms above Mawïew gorge[8]

The rising fog has brought its blight

Withering our sense of shame, of right,

Are there voids of darker menace

Than those we call the human heart?

White ants that fly through air and light

Did once emerge from the termite’s hole

Like fiendish scourge of hornet, wasp

Who from dark places emigrate,

But Integrity and Honour shun the confines

Of Pandemonium’s night[9]

For a fistful of silver men sink their teeth

Tight the clench, unrelenting the grip

Like Mighty Mammon defeated bowed

All are seduced by the Goddess Fair

From heavenly highways lined with gold

To buried seams in Hell’s Nine Tiers

Silver cowries Her brilliant lenses[10]

She blinds the tempted with her dazzling vision

Tapestry threads of tortured logic

Which the gold? Which twist the maggot?

For Falsehood’s stature to command respect

She rips the mote from the eye of Truth

“Timidity hobbles adventure”, so we are told

Yet renegades run riot respecting no bounds

Hills avalanche, waterholes seethe

“Heat scorches advance, cold freezes retreat”

Rulings judgements exchanges intense

All blinded by the silver slime

The scion dines with rival groups

Purse strings hang lax, no taboo restrains

Where dissension prevails and discord persists

It is there that he seeks to add weight to his gold

While Truth has her abode in the City of God

On the skin of the earth untouched by shame, blatantly bulges the purse of man[11]

Man’s greed is now a gluttonous sow

(A pouch engorged about to rip)

A flatterer adept at placating egos

Swelling the hide of the sun-eating toad[12]

And when like a leech she measures each step

Souls shrivelled by fear stand mutely and watch

The Silver Cowrie is armed with teeth

His grip a vice, does not let go,

A watchful kite who circles slow

A wasp unhurried for he knows… a bite at a time is all he needs[13]

And as tiger fierce or the great She-bear

What monstrous acts could he then perform?

When man becomes a being from Hell

Sustaining blood from there will flow

Vindications produced to bludgeon, stun

Dry lightning leaps in blinding red

Thunder bolts aim to pierce the joints

Triggering tumult in the nerves

Goodness stunted, Evil monstrous

Broken the laws of God and Man

Old voices say a time will come

When Man will swim in the ox’s mire

And scale the tops of pepper plants[14]

The Silver Cowrie is the Thlen

Greed’s a chasm like the Mawïew ravine

A depth no one can hope to fill

Yet he who endures, strives to hold on

In whom the will to good remains

To him the vision will be tendered

Of wind-stirred palms above Mawïew gorge

Thus as he journeys round the world

Man sinks and drowns in waters dark

His face begins to dim and darken

The rising smoke it thickens chokes

Though many a voyager may stay afloat

Far, far away let me escape!

—–

[1] A reference to the folktale where the ox lost his upper teeth for not carrying out God’s explicit instructions warning human beings not to be wasteful with their natural resources, more specifically asking them to cook only the required amount of rice so there is nothing left to throw out. On his way to deliver his message to mankind, the ox was plagued by insect bites, an agony finally relieved by a crow alighting on his back to peck and devour the irritants. But hearing about the message the ox had to deliver, the crow was alarmed for she feared her tribe would lose a source of food in the form of rice offerings left at cremation grounds for departed souls. So she persuaded the ox not to carry out God’s bidding. Grateful to the crow the ox agreed. But God was enraged when he found out that the ox had disobeyed, and struck the ox a huge blow knocking out all his upper teeth.

[2] To give birth to and thus jettison the evil he carries within himself and thus be born anew. Or, to give birth to the Knowledge symbolised by the script he had swallowed and lost in the Great Flood.

[3] This is a reference to the old Khasi explanation for an eclipse. Khasis believed the phenomenon was caused by a giant toad or frog in the sky swallowing the sun and moon.

[4] “indwelling soul” is my equivalent of the phrase “ka Rngiew”, different from U Rngiew, the embodiment of evil in Chapter 8. The word/concept is difficult to translate. It is sometimes likened to an aura or compared to the Greek psyche meaning “soul” or “spirit”. Khasis believe that every person is endowed with a vital life force that waxes and wanes in strength. It is this invisible essence which the onlooker senses, and then accordingly tenders respect or heaps derision.

[5] Soso Tham uses the word Kyiaw (Mother-in-law) but I have used Queen as that more accurately aligns with an English sense of what the poet is trying to convey. To a Khasi kyiaw would make sense from the point of view of the social custom where once married the man leaves his maternal home and becomes part of his kyiaw’s home, where she is traditionally revered as the caring queen of the family.

[6] This is the area known as Lyngngam in the South West Khasi hills where the people, also known as the Lyngngam, are of mixed Khasi and Garo ancestry. Garo is a language of Tibeto-Burman origin while Khasi belongs to the Mon-Khmer family of languages. Soso Tham does use the word Lyngngam, but to maintain the rhythmic pace of the line and to convey the connotation of the word Lyngngam, I have used “borderlands”.

[7] To the Khasi there cannot be any substitute for rice as a food staple. A person who goes out to earn their living to feed the family is one who goes in search of rice—the only grain that can provide sustenance and satisfaction!

[8] A ravine near Sohra so deep that filling it with soil would be a nigh impossible feat. See also the penultimate stanza in this section where man’s greed is compared to “a Mawïew gorge” that cannot be filled.

[9] Milton’s Paradise Lost made a deep impression on Soso Tham.

[10] The Khasis once used cowrie shells as currency in trading activities.

[11] Through sheer chance I discovered that the Khasi word pdok has two meanings—the gall bladder and a purse. Maybe it has more? So another possible translation of this line could well be: “Man’s gall exposed on the skin of the earth”. I feel both meanings of the word “gall” feed into Soso Tham’s use of the word as conveying a totality of experience which accounts for the darkness enveloping the poet’s soul and contributing to his sense of foreboding.

[12] This line vividly conveys the image of uncontrollable greed, especially if one compares the size of the toad to that of the sun.

[13] Having watched the steady, repetitious, robotic up-and-down movement of a wasp’s head as it chews wood to build a nest, I appreciate the economy of Khasi as a language, for the phrase “roit roit” which Tham uses to describe this process is all that is needed to convey to the Khasi reader or listener the entire concept and rhythm of the wasp’s single-minded attention to his task. In English however I have had to use more than two words to convey this effect.

[14] Lines 4–5 in this stanza refer to the Khasi’s deep belief that the only wealth which matters is that of the spirit. Any neglect or violation of this cherished belief diminishes human stature to such an extent that it is possible for a man to metaphorically swim in water-hollows created by the hoof prints of cattle, or enable him to clamber easily to the top of slender chili plants. A reliable source, Bah Khongsit (see Acknowledgements) however also informed me that his father used to grow chili pepper plants which had thick roots and sturdy stems. These were vastly different from the slender chili-pepper plants familiar to most of us. Apparently it was possible to lean against these robust plants without the plant bending under pressure.

5. U Rngiew / The Dark One[1]

Scenes from myth along with multiple images of terror and menace are used to describe how the twisted nature of evil wreaks moral havoc. Here is a place that is dark and forbidding where the deadening sense of miasmic heat and torpor is inescapable. Images of sick elephants tottering helplessly into murky swamps and serpents coiling around every tree add to the atmosphere of malaise and prowling treachery. Nightmares peopling the Khasi imagination are given free rein, like the pursuing “hounds released by their Mother Fear”. The ruling deity and embodiment of all evil is The Dark One—U Rngiew—shape-shifter par excellence possessing the ability to lure and entrap.

![]()

Far from the city where humans dwell

A forest grows where the Dark One lives

Here the face of the Moon is dark

Here the eyes of the owl burn bright

Eternal are the clouds that shroud

This hometown of the Nongshohnoh[2]

Here it was since Time began

That Evil came to dam a swamp

In tottered elephants seizured, sick

Darkly heaved the ponderous ooze

With kindling from Satanic Fires[3]

The prowler lights his furtive path

A squelchy mire which smoke calls home

Where toxic fumes douse glowing fires

Here one finds there’s no escape

From the dragging-down oppressive heat

Indecision with her lonely face

Has feet imprisoned in the clay

Everywhere the air reeks stench

Serpents wrapped round every tree

In every chasm every gulf

Evil’s jaw a trap full primed

Oh you who throng the vault of heaven… listen feel and wonder why

An uproar churns in Earth’s dark belly

Feline offspring his face soot-black, knocks and begs from door to door,

Shape-shifter from the Hill of Death

A stag one moment, a tiger the next

Stampedes wild bison which scatter confused,

A goddess at times, a monster at others

The day before a strand of pearls, today a serpent’s coil

Hound with flung-bone pinion in his throat

Transforms with ease to a docile lamb

His coat is soft… so tender-soft

His words beguiling gentle flow

Yet herded to the pen at dusk

Straight he streaks to the deepest cave

The Rakot’s bones hard limestone layers

Her blood congealed to coal,

Khyrwang-draped U Ramshandi,[4]

His mighty club heaves to anoint

Head over heels his victims roll

Roars the abyss in vast applause!

A black wind rises in the forest

With every breath of the Serpent King

From shadow worlds he drags down low

Ka Shritin-tin, Ka Mistidian

Along with seizure-blighted vultures

Oh what these spectres! Ram Thakur![5]

Meanwhile Ka Lapubon, Lotikoina

Sing their spells in the dead of night

Release caged torment long confined

In the prison owned by the King of Death,

Words they use to hook to bait

Nine times over Truth is twisted, turning cartwheels without end

An unblemished Name is a mighty shield

Protects the unkempt destitute[6]

“God of Truth”—“The Nine Above”

“The Words of Those Who Came Before”,[7]

While God calls man to heaven above

U Rngiew drags him down to Hell’s Nine Tiers

Rogue elephant U Pablei Lawbah,[8]

Trumpets long from forest fringes

The untouched beauty of the moon

Forever bruised and blemished since

The medium’s speech a bewildering babble

Forked the tongue of this Red-Crested One

Towards him sludges the Umsohsun[9]

Turbid with the rush of rot

The human face tough-skinned, dull-browed

A mask for evil locked within

The red-headed god lifts to his lips

A lavish feast of toads and frogs

The nine clear springs will soon run dry[10]

And so will haunting pools of tears

Demonic howls will rent the skies

A clamorous din will swell the earth,

When man ingests all that he can

That day will be his last on earth

Kyllang, Symper of might profound[11]

Will either drown or float away

The hardest flint of stubborn mould

Will detonate in a firestorm

The inferno consumes Bah-Bo Bah-Kong[12]

The Black Serpent King is drenched in red!

His peeling skin with ease sloughs off

Child of change he now can fly

Alone he circles shadowy lands

And then at last a fire-serpent

Wicked heart of toxic envy

Burns reduces all to ash

At the city-gates where The Dark One lives

Stand barking dogs bred to attack

Chants are heard, apparitions haunt, creepers hide malignant imps[13]

There also thrive—fevers, pestilence perplexity plague;

The Sanctified Spirit offered to all[14]

By he now ordained—“Venerable Uncle, Respected Father”

Mindless Terror the Cavern King

Night and day He seeks out prey

In every home a pack released

Hounds unleashed by their Mother Fear

From hellish gutters come these dogs

Howling devils who roam the earth

Like the hornet, ravenous demon

U Rngiew delights in startling prey

(In the crook of her arm, secure on her hip, Death safely holds her child Lament)

He gorges on from dawn till dusk

Through Spring and Summer, Autumn, Winter

Day after day and night after night, helplessly caught in the grip of greed

Stirring flames to wild abandon

The Serpent’s hiss illumes the night

From tops of boulders rough and craggy

The grey owl moans “Kitbru, kitbru!”[15]

Unbroken howls on snow-capped peaks

Jackals wailing without end

Many are those who hide from him

They burrow deep into their beds

In homes in caves in tall spared grass[16]

They sleep by day, are awake by night

Women, children fear the dark

Sinister shadows, shaggy-haired… menace prowls outside their doors

From deep within the midnight dark

The devil’s blaze sheds fitful light

On the dancing wraith upon a Phiang,[17]

Kyndong-dong-dong goes the tapping drum

And when the jaws are poised to clamp

Strange markings streak the earthen pot

A windrush stoop to Pamdaloi[18]

From where he journeys round the world

He hovers in wait by that open door

Once inside, a vessel his haven

The life of their souls entrusted to him

Forever a king in bliss and contentment

In ancient hamlets back in time

One word echoes—“Curse!”—it calls

In those dwellings where he lives

Light struggles hard to defeat the dark

Hope takes flight, rejects, abandons,

The homes of the Thlen—they wither die out

Red-hot spike lodged in his craw[19]

They pulled him out of his ancient cave

They chopped his body into bits, to feast on his remains,

But a morsel forgotten grew into a seed

Invasive hungry rampant wild

Spawning swarms in sites undreamt—those caverns of the human heart

Where pitch-black are the sun and moon

Far reaches where the wraith sheds tears

The lovely maiden a wandering recluse

Why does she roam wild-eyed alone?

The serpent’s coils are tightly wrapped

Around the blooming Amirphor.[20]

—–

[1] As mentioned earlier, “U” in Khasi is masculine and “Ka” is feminine. So the Dark One, a malignant being, is a “he”. Usually “rngiew” or “ngiew” is associated with the sinister as in “syrngiew” (shadow) or “i ngiew” (looks or feels dark and disturbing). Interestingly however “Ka Rngiew”, therefore feminine, has little to do with “U Rngiew” or that sense of “ngiew”.

[2] Henchman employed by families who worship the Thlen—the man-eating snake. The word literally means “he who does not hesitate to strike (a blow)”, once he has cornered victims whose blood is needed to placate the wealth-providing but ever-hungry Serpent Deity.

[3] The “kindling” used is actually dry bamboo—“prew”—which burns easily and brightly. Bamboo grows widely in the Khasi and Jaiñtia Hills and is a wonderful natural resource with a variety of practical uses.

[4] Limestone and coal are minerals found in the Khasi and Jaiñtia Hills. The word “Rakot” is the Khasi corruption of “rakshasas” the demons of Hindu mythology who, as shape-shifters, can be either male or female. According to H. W. Sten in his book Na Ka Myndai sha Ka Lawei, Tham here illustrates the concept that evil appears in different guises, such as The Dark One and U Ramshandi (a blood-thirsty deity). As a sorcerer Evil works his dark magic even on heavenly beings like Ka Shritin-tin, Ka Mistidian, Lapubon and Lotikoina who become agents of his dark arts. See ns. 5 and 8 below for more information. Khyrwang is a piece of cloth woven from eri silk (now also known as ahimsa-silk) worn as a shawl by men and wrapped sarong-style by women. Its distinctive stripes make it instantly recognisable as a traditional product of the Ri Bhoi District of Meghalaya.

[5] Ram Thakur could be (1) the Hindu God Ram. Or (2) Ram Thakur who lived between 1860 and 1949. His followers believed he was an avatar of Truth, a deity who appeared in human form to bring salvation to all. Given that this stanza is about false gods and demons, I feel Soso Tham here is not calling upon God Ram or Ram Thakur for help. To Tham the devout Christian and a patriotic Khasi, Ram Thakur represents a baneful threat. As S. K. Bhuyan writes in his introduction to Ki Sngi Barim, Soso Tham’s “… patriotism has led him to an overwhelming bias for the manners and traditions of his native land”.

[6] According to Sten, Tham is probably referring to the manipulative Pablei Lawbah (see footnote 8 below) who was protected by a number of eminent citizens of Khasi society who believed him to be a (Khasi) god-incarnate.

[7] The words within quotation marks are supposed to be those uttered by Pablei Lawbah whom Soso Tham denounces as a false Messiah.

[8] Again according to Sten, Tham here intertwines two stories—that of U Dormi called Pablei Lawbah by his followers, and U Rngiew. U Dormi was a cult figure who proclaimed himself the reincarnation of U Sohpet Bneng and was by some looked upon as a deity. Soso Tham was horrified that a mere human being should call himself a God (Pa means father and blei means God) and thus run counter to the original Khasi belief in the one and only Creator-God. So the specific details relating to Pablei Lawbah as being the medium through which God spoke to the people, are recounted here to explain the poet’s wrath at an impostor who, as a medium, is supposed to have spoken in the voices of alien deities like Ram Thakur (see footnote 5 above) and (now) evil female spirits (Ka Shritin-tin, Ka Mistidian, Ka Lapubon, Ka Lotikoina). With his “forked tongue” he bewitched a susceptible audience. Pablei Lawbah is a travesty of the real Saviour—the Noble Rooster who according to Khasi belief, interceded with God. In the Christian context he was a Pretender to the throne of grace on which sits Christ the saviour. Pablei Lawbah is like the mythical U Rngiew who also adopts several guises to lure and ensnare his unsuspecting victims.

[9] A locality in Shillong named after the stream Umsohsun (Um means water). Filthy waste from part of the town drains into the stream which consequently never runs pure.

[10] These are the nine springs on Shillong Peak from which our rivers take their being.

[11] Kyllang is a dome of granite rising from the countryside of Hima Nongkhlaw, and Symper found in Hima Maharam, is a hill covered in lush forests. Hima means kingdom or fiefdom. Kyllang and Symper are said to have been the abode of two mountain spirits, brothers whose rivalry led to a bitter battle recounted in a legend that explains the particular physical aspect of these two hills. See Kynpham Singh Nongkynrih’s Around the Hearth: Khasi Legends, pp. 80–83.

[12] The legendary forests on the slopes of Bah Bo Bah Kong in Narpuh (Jaiñtia Hills) are now no more thanks to the unholy alliance between greedy politicians and cement companies. What Tham thought unimaginable in his lifetime has tragically come to pass.

[13] Khasis tell tales of a will-o-the-wisp creature that lures unsuspecting travellers. One traveller managed to wound one such spirit with his arrow and, following the trail of blood left by the spirit, finally came to a dead end by a creeper where the evil sprite is said to have taken refuge.

[14] Devotees of the Thlen are said to set aside rice beer for a year by which time the drink is so strong as to cloud the drinker’s judgement, emboldening him to commit murder without a shred of regret. This is the “consecrated spirit” given to their henchmen—the nongshohnoh. Rice beer also forms part of the main Khasi socio-religious ceremonies (weddings, naming ceremonies, death). All these are conducted in places that have been blessed and designated as hallowed and sacred. The use of this staple ritual to further evil underlines the twisted blasphemous nature of U Rngiew and those who purportedly worship the Thlen.

[15] In keeping with the ominous nature of night, the call of the owl—“kitbru, kitbru”—definitely carries a sinister message. Kit means carry away and bru means people.

[16] The “tall spared grass” refers to swathes of grass left uncut and never cleared for cultivation or eaten by grazing animals. It is usually found on the peripheries of villages. The grass follows its own cycle of life, death and regeneration, thriving on the rich organic matter into which it breaks down. It is so lush and thick that it is said to make a comfortable bed for a tiger.

[17] Phiang is short for “Khiewphiang”, a water pot found in most Khasi homes. The “he” referred to here is the Thlen. It is said that when devotees bring him offerings of human blood, the victim appears as a spirit dancing to the accompaniment of drums on a silver plate, casting a shadow on the side of the water pot.

[18] The name of the village where the Thlen’s cave is located. The verse shows how evil personified by the Thlen and U Rngiew, enters homes whose inhabitants have an intense desire for wealth. Again a reference to the legend of the Thlen, who was nurtured by humans who tried unsuccessfully to destroy him—a metaphor for man’s endless struggle against the lure of wealth.

[19] Another reference to the legend of the Thlen whose own greed ultimately caused his downfall. Accustomed to being fed human flesh he opened his huge mouth to receive more, realising too late that a red-hot stake had been hurled into his throat. He died in torment and it is believed that his writhing caused earthquakes so strong as to alter the topography of the land forever. Myths about the history of the land ascribe the Khasis’ fold mountains to this event. See Nongkynrih, Around the Hearth, 64–72.

[20] The word is probably Sanskrit or Persian in origin. “Amar” in Sanskrit means immortal and “Amir” in Persian is one whose soul and memory does not die. “(Amir)phor” would be the Khasi pronunciation of “phol”or “phal” which in Hindi means fruit. So perhaps this is a reference to an Immortal Fruit or Flower, which makes sense within the context of cultural jeopardy that so troubled Soso Tham.

6. U Simpyllieng / The Rainbow

Out of relentless darkness hope emerges and here we begin to feel the calm benediction of light. Although the rainbow as a symbol of hope is appropriate in any culture, in the rain-lashed Khasi Hills where the Monsoon exults in unleashing its power, the colours of the rainbow arcing against freshly washed skies will obviously have a special resonance. Nature and Myth both underline the constancy of hope and mercy, provided mankind repents of his sin of pride and seeks forgiveness from his God.

![]()

The face of the earth polluted by sin

The God within has taken flight

“Ascent” “Descent” forever ceased[1]

A people gripped by terror fear

Blinded choked by infernal hordes

“O where is He, He whom we love”[2]

Wisdom, Knowledge, Contemplation

Blindly stumble in the dark,

A widowed mother children held close

Cursed by memories helpless, alone.

Lost to us the Amirphor

All that is left is the Ekjakor[3]

The world lies awake at the witching hour

Stars drown themselves in Hell’s deep void

Throughout this black impenetrable night

Grant us relief O Morning Star

You who with the rooster’s clarion

Welcomes the light that will drench the world

Crippled by affliction, crushed by illness

We glimpse the rim of earth’s dark belly,[4]

As when we encounter tiger bear

Our souls recoil and shrink with fear

The ceremony of colour now faded frail

“Rites, divinations—confusion confounded!”

What then is Right and what Transgression?

Though fervent the atonement, clan numbers decline

—“For Me! For Me!” Insatiable the demons, insistent the clamour[5]

The dignity of sacrifice most solemn profaned

Dried is the nectar, just the comb remains[6]

“O hear us, we pray! You who made us, placed us here on earth!”

As children die

Deceived betrayed[7]

Maggot, Fly and sickly Vulture

The only clans to grow and prosper

To lift the Shyngwiang to their lips[8]

Conducting rituals, performing last rites

“A basket of seeds yields a mere khoh of grain[9]

Much you will spend, but meagre your gain

One at dawn another at night

They give up the ghost so that I might live

For that’s how I’m fed, and from hunger am spared.”

So sings the crow as she circles above

Those offerings of rice that are left for the dead![10]

The Midnight King ascends the throne

The world spirals down into Circles of Hell

Man wanders the world to look for a way

To rebuild restore the Covenant broken

For light to rise from deep in the dark

And for an insurgence of song to break out in his heart

Flames from the altar will rise to the skies

To Heaven man lifts his troubled gaze

When will the Dawn unveil herself?

When will the firmament blush a deep red?

And how from amongst a cohort of devils,

Will one stand upright and alone to face God?

One who strives to seek and appraise

Comprehending the mystery of divinations and rituals

Who evaluates, debates to challenge his Maker:

“Freely, generously, give of your blessings!”

He will plead for himself, stand up for his clan

To wrest divine pardon for sins and transgressions

“To shoulder sin, to bear the yoke

Make strong Ka Rngiew, to cleanse the curse”,

These the words of God our King

Heard at the Durbar of Thirty Beasts,[11]

“Until the Prince of Song arrives[12]

Who consents to bear pain to save mankind?”

So spoke our God our Lord above

What answer will the Durbar give

In silence long the hushed world sat

Eyelids drooped beasts fell asleep

One question lingering on the lips of man

“The Prince of Song, when will he sing?”[13]

Stop! Now listen from Ka Krem Lamet Ka Krem Latang[14]

Keeper of his Word, the Rooster speaks:[15]

“Until the day of the Awaited One

Come what may I will bear the burden

To spare mankind eternal woe

When before his Creator God he stands.”

Thus he addressed the assembled Durbar

Fearless he stood holding fast to his word

Crossing the threshold of the Sun’s domain

He claps his hands and she wakes from sleep

And when the rooster thrice had crowed

The earth once more was bathed in light

The land, the soil began to bloom

Trust returned fear exorcised

Foreboding sank in Ka Diengïei

Along with her demonic troops

Vivid all auguries, signs and predictions

Divinations and reckonings deciphered made clear

A shroud now lifted from the face of man

Who once again “ascends” “descends”

Heaven and Earth united as one

For man stands upright to appease his God

Peace shall reign throughout the land

Visible once more the King of the Skies[16]

Gleam of sky on rock we’ll see

When sun-showers stop and fade away

Dense dark clouds in fear retreat

When the Rainbow rises in the sky

When man grinds Satan underfoot

He then becomes a Child of God

When long ago the earth was pure

Dark was both the Sun and Moon

But through the dense relentless night

The Star of Hope refused to die

The Gift of Mercy man receives

When before his God he bends his knee.

—–

[1] Referring to the time when the golden ladder, the “mediator” between heaven and Earth on U Sohpet Bneng had not been removed by God and human beings could move easily between the two domains.

[2] “He” is the saviour. As Soso Tham was a devout Christian, one assumes he is referring to Christ.

[3] A mythical Dragon/Serpent.

[4] The earth here is a grave/a tomb—although the earth is also seen as the womb of life.

[5] Khasis believe that illness and affliction are either signs of divine or demonic visitations. A person’s health could only be restored when the particular god or, as in this case demon, has been appeased.

[6] Honey, especially that collected from orange groves in the Khasi Hills, is one of Meghalaya’s most prized products. Honey is a metaphor for sweetness and plenty.

[7] A reference to the folktale of the ox punished by his Maker for his disobedience.

[8] A flute played during religious ceremonies.

[9] A khoh is a basket with sides tapering to a point and carried on the back with the aid of a head strap. It is used to carry a variety of goods including market-produce, firewood and pots of water from a spring or communal tap.

[10] As part of the funeral rites, offerings of rice are left for the deceased at cremation sites, thus providing food for the crow, the bird who for personal gain persuades the ox to lie to mankind.

[11] Thirty is a number Khasis use to indicate a great many.

[12] Simpah/Simkaro is the name given to a gifted Intercessor. Sim means bird, pah means song or singing. I have translated the word into “Prince of Song” but to fully understand what “Song” means, it is important to remember that, among Khasis, songs are outpourings which have their root in religious observances.

[13] Sim-karo (like Simpah): this term is a metaphor for a man elected as leader for his altruistic and trustworthy qualities. He is seen as the agent of light and transformation as willed by God.

According to Sten (p. 77), Khasis see the root of their creativity in their outpourings of prayer and thanksgiving to God. It is through these acts of worship that Khasis express their understanding of their place in this world and their relation to God. Thus poetry is linked to the sacred and the divine, and the poet is in many ways God’s agent whose song draws those who suffer under the yoke of sin back to the divine.

[14] The Cave into which the Sun retreated in anger, depriving mankind of light.

[15] Again refers to the same legend of the Rooster offering himself as a sacrifice to the Sun so that she would forgive mankind and restore light to the world.

[16] “King of the Skies” refers to either the rainbow or Christ. Based on the words ascribed to the rooster in verse 13 (“Until the day of the Awaited One/I’ll bear the burden come what may…”), Sten maintains that Soso Tham saw Christianity as the final flowering of the indigenous Khasi belief in a saviour releasing the world from the darkness of sin. See Sten, Na Ka Myndai, p. 79. The underlying belief of both faiths is hope and salvation through a “mediator”.

7. Ka Ïing I Mei / Home[1]

A more literal translation of the title is “The House that Belongs to my Mother” or “My Mother’s Home”. Here “Mei” refers both to the biological mother and to the poet’s homeland, for both have nurtured the poet’s being. With the dawn of hope and light in the preceding section it is natural that the poet now describes what it feels like to be home. He goes back in time to his childhood and to the daily rituals where the sacred codes of life are affirmed. Finally, he moves on to describe the rituals of death with reference to the concluding lines of Ki Sngi Barim, where the poet talks of arriving at the House of God—the everlasting mother of all homes and sanctuaries. But what is always characteristic and remarkable about Soso Tham is that his presentation of the most weighty and serious of subjects is endowed with an inescapable energy. Since for Soso Tham his culture is so obviously alive, he cannot but describe it in dynamic and vivid terms. Even the rendition of ceremonies for the dead is undeniably joyful.